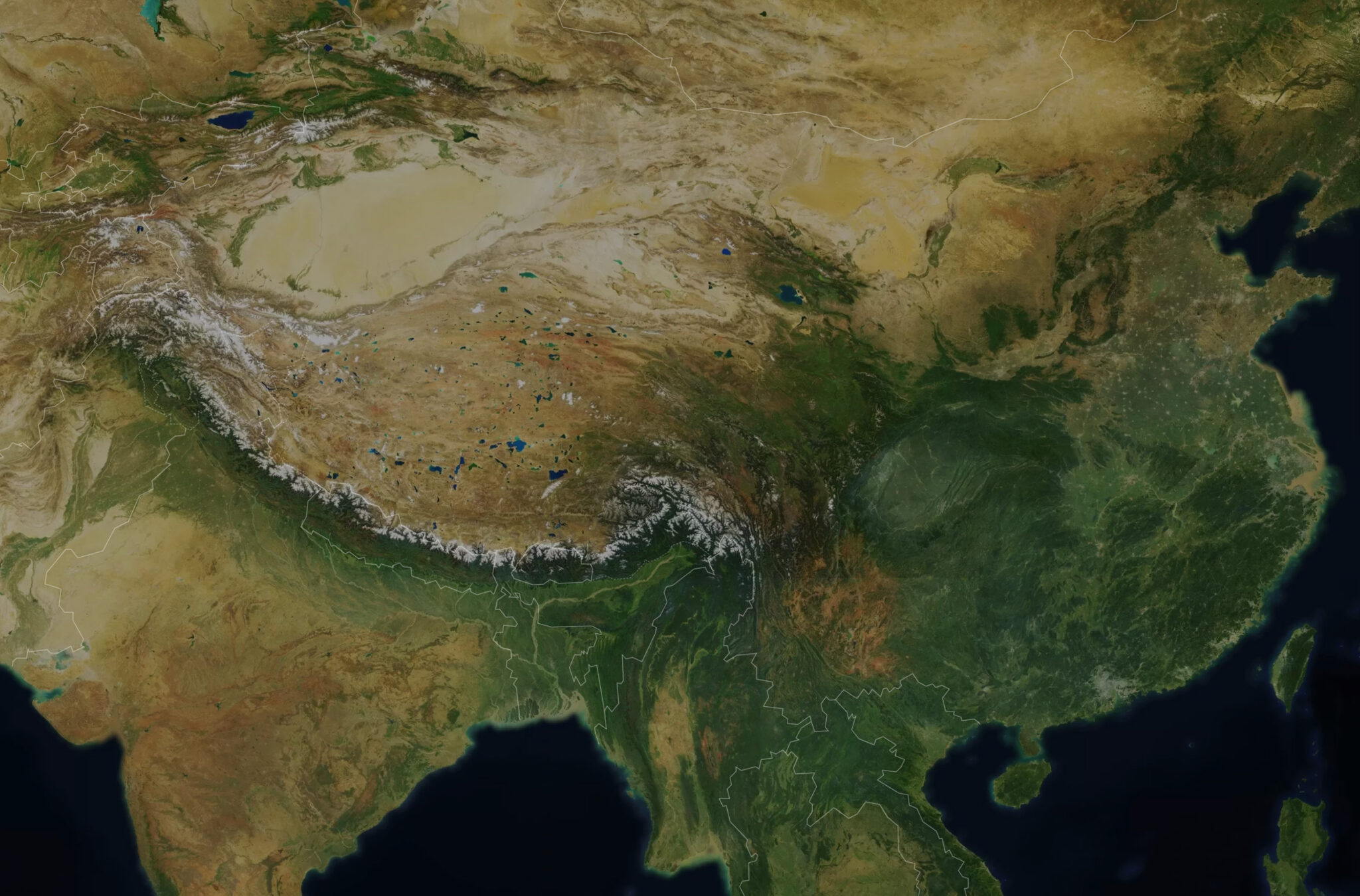

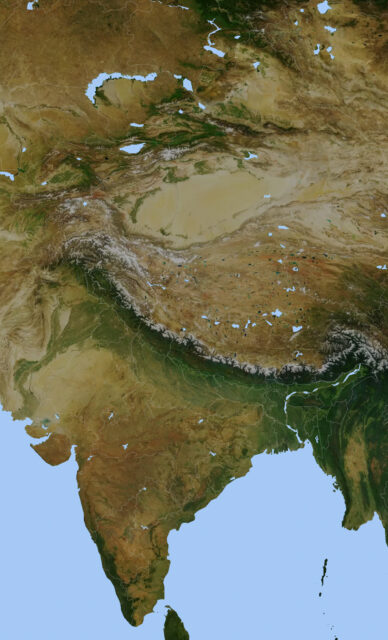

Himalayan art spans the artistic traditions of the diverse regions and cultural spheres of the greater Himalayan mountain range, the Tibetan Plateau, and connected areas of . It bridges and traverses these distinct regional spaces through connections made and maintained by pilgrimage, trade (economic ties), military/political expansion (conquest), and institutional connections.

Tibetan Regions Permalink

From the fertile valleys of the Tibetan Plateau, Tibetan rulers of the 7th to 9th century expanded their domain into an empire that absorbed parts of Central Asia, allowing them to gain control of important trade routes. According to traditional historical accounts, Tibetan rulers embraced , establishing this foreign faith as a state religion of their land. Tibetan rulers, translators, teachers, artists, and lay people actively conveyed their Buddhist culture to the regions of Inner Asia, including the people, the , and courts in China.

Today, Tibetans primarily live on the Tibetan Plateau, which sits between the Himalayan mountain range and the Indian subcontinent to the west, Chinese cultural regions to the east, and Mongolian cultural regions to the northeast. This includes Western Tibet and the central Tibetan regions of and , now part of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) of the People’s Republic of China (founded in 1965); and the eastern Tibetan regions of and , now divided between the TAR and the Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan. Currently, Tibetan cultural regions with prevalent Tibetan Buddhist culture also encompass the Himalayan regions of north western Nepal—Dolpo and — and western Himalayan areas of Ladakh, in Indian-administered Kashmir, Spiti in Himachal Pradesh, and the former kingdom of Sikkim.

The Castle and Temple of Yumbu Lagang, Yarlung Valley, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); founded ca. 6th century; photograph by Vladimir Zhoga

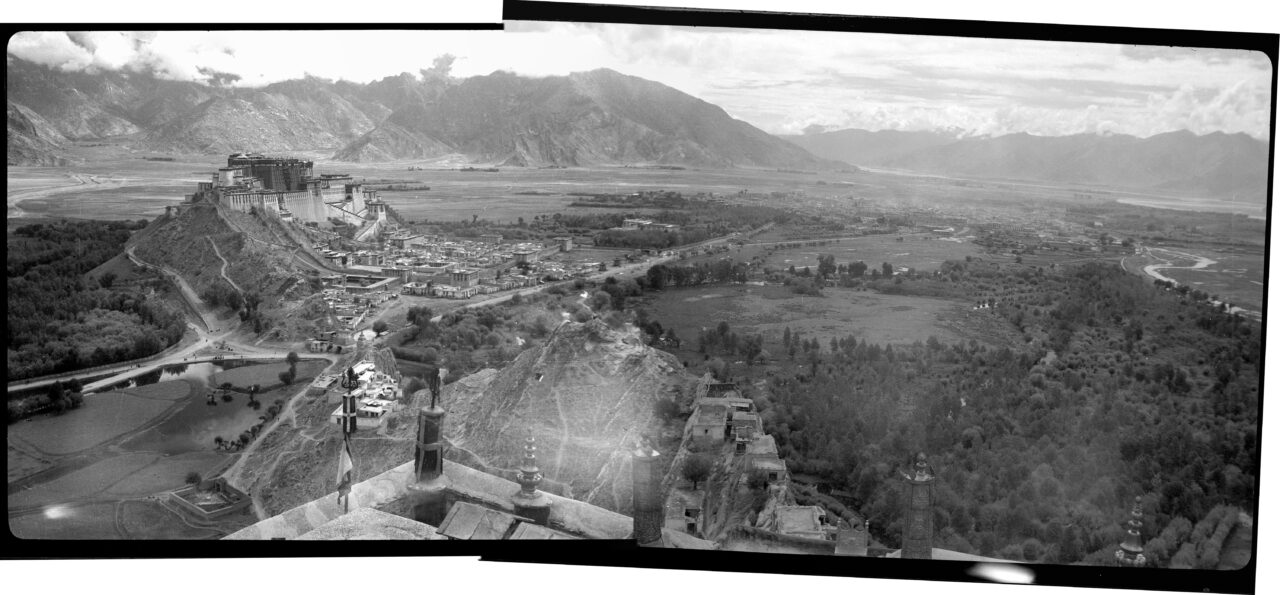

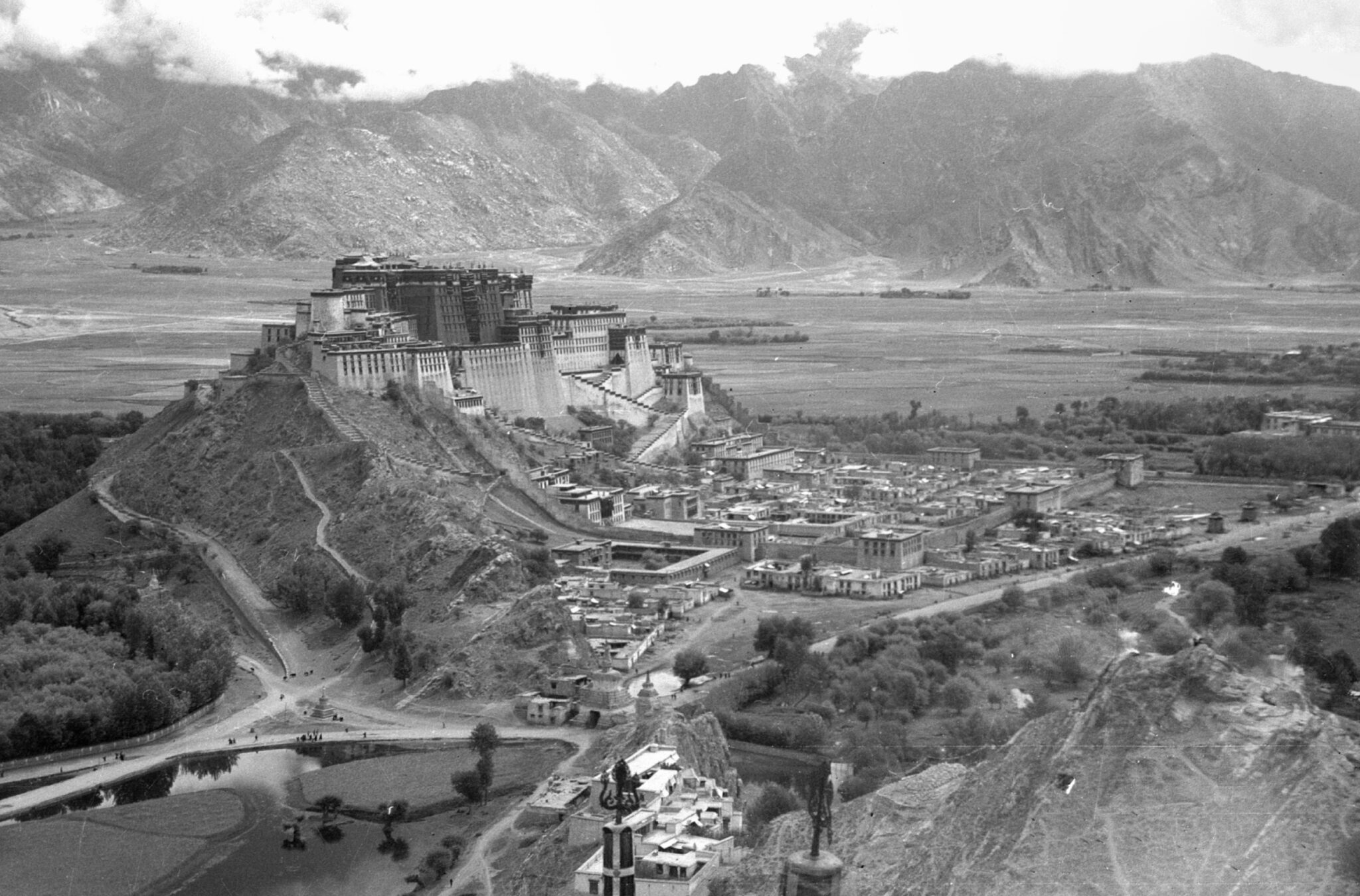

Photograph by Prodhan (Sikkimese; dates unknown); The Potala Palace, Lhasa: The Seat of the Dalai Lamas; 1948; film negative; courtesy of Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente (Is.I.A.O.) in I.c.a. and Ministero Degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale; Neg. dep. 7710/02 + 8037/05 © Museo delle Civiltà

Pelkhor Chode Monastic Complex; Gyantse, Tsang region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); ca. 1427; photograph by Shengnan Dong, 2021

Vairochana and the Eight Bodhisattvas; Markham, Tibet (present-day TAR, China); photograph by Tsering Gyalpo

Ambulatory of Phuntsok Ling Monastery, Tsang region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China), showing the northern wall with Life of the Buddha Mural, panel 7; photograph by Andrew Quintman and Kurtis R. Schaeffer, 2011

Northeastern India Permalink

As the cradle of , northeastern India was and remains today the region of sacred Buddhist sites for pilgrims. These places include the most important site of the Buddha’s awakening, Vajrasana at , and major centers of learning, such as Nalanda . Up until the late thirteenth century, India was the birthplace of a significant amount of Buddhist material and visual culture. Buddhist teachers, visiting monks, traders, and pilgrims carried portable sculptures, mementos from sacred sites, texts, and other objects back to their homelands in Tibet, western Himalayan regions, Nepal, and beyond.

Mahabodhi Temple at Bodhgaya, India; photograph by Christian Luczanits

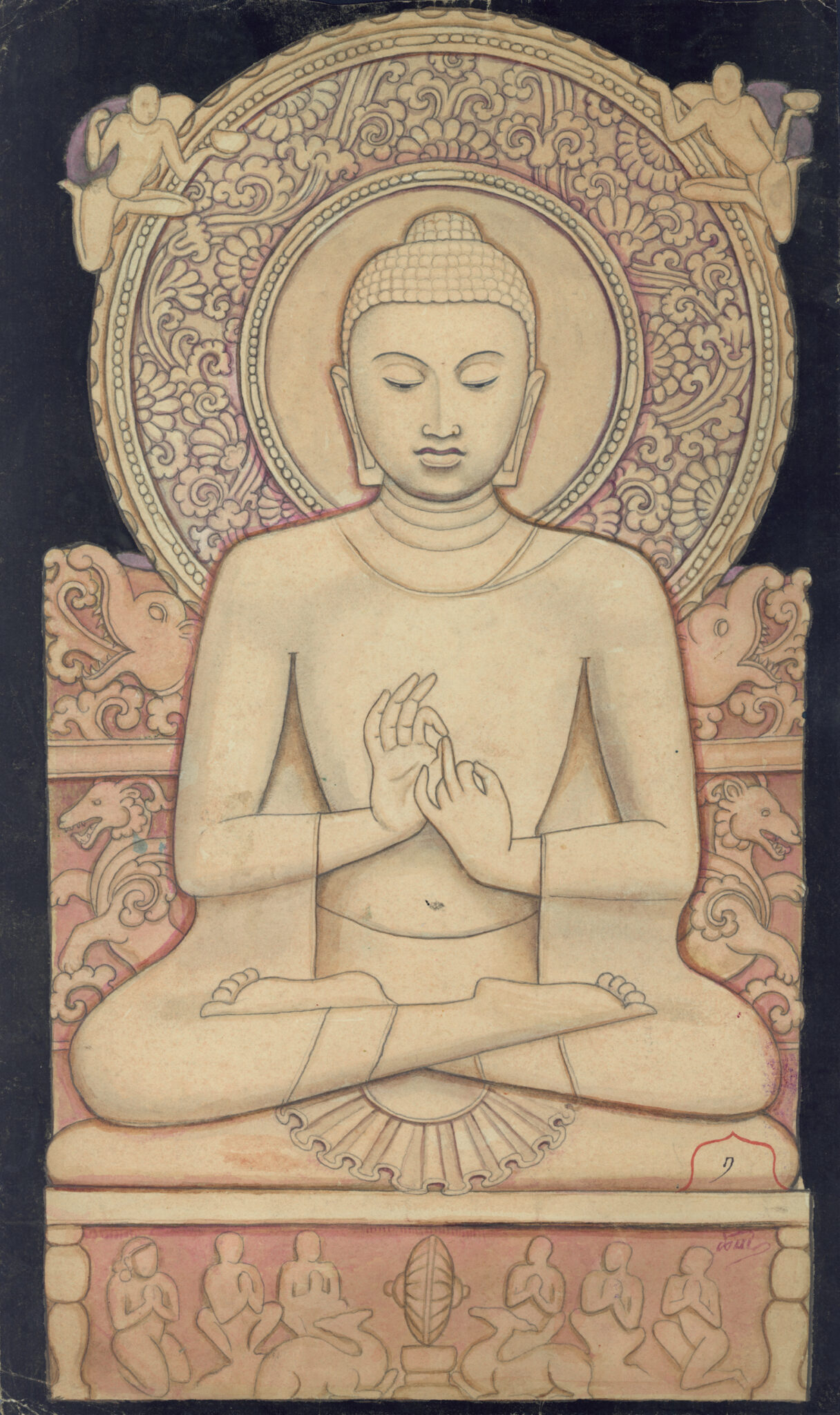

Gendun Chopel (Tibetan, 1903–1951); Sarnath Buddha; India; ca. 1940; watercolor; 14⅞ × 9 in. (37.8 × 22.8 cm); Private collection; image after Xiong Wenbin and Zhang Chunyan, eds. 2012. 2012 nian de zhui xun: Xizang wen hua bo wu guan Gendunqunpei sheng ping xue shu zhan 2012 年的追寻: 西藏文化博物馆根敦群培生平学术展. Beijing: Zhongguo Zang xue chu ban she; photograph courtesy of Latse Library

Naresh Kumar Verma (Indian), design, and Lopon Lhundrup (Bhutanese), construction; Statue of Guru Rinpoche; Samdruptse, Namchi, Sikkim, India; 2004; concrete base with gilded bronze and copper body; height 135 ft. (41.1 m); photograph by Amy Holmes-Tagchungdarpa

Kashmir & Western Himalayans Regions Permalink

As a fertile valley nestled between the highest ranges of the Himalayan mountains, Kashmir was a revered kingdom of Buddhist learning, arts, and cultures from the 8th to the 13th century. Kashmir was one of the main sources of in the western Himalayan kingdoms, which encompassed areas in present-day northern India—, Zangskar, Spiti, Lahaul, and Kinnaur—and the region of western Tibet known as . Kashmir was a significant destination on trade routes that traversed the neighboring western Himalayas and connected western and central Asia. Until the 14th century, Kashmir was an important center of esoteric, or Tantric traditions and Buddhist culture, where Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhists went to study. They also invited religious teachers and artists to their newly built temples, and brought back home books and images.

Rock Carving of Four-Armed Bodhisattva Maitreya; Mulbekh, Ladakh, India; ca. 10th–11th century; stone, height approx. 25 ft. (7.62 m); photograph by R. Linrothe

Manjushri with Mahasiddhas, right niche of the Sumtsek Temple; Alchi, Ladakh, India; ca. 1220; mineral pigments on clay; height approx. 13 ft. 1 in. (40 m); photograph by Jaroslav Poncar

The fortified complex of Wanla viewed from the northeast, with the three-story palace on top of the peak to the northwest (at right); Wanla, Ladakh, India; gradual construction since at least the 13th century; approx. 300 × 300 ft. (90 × 90 m), excluding the outpost to the southeast (at left); photograph by Nils Martin

Nepalese Regions Permalink

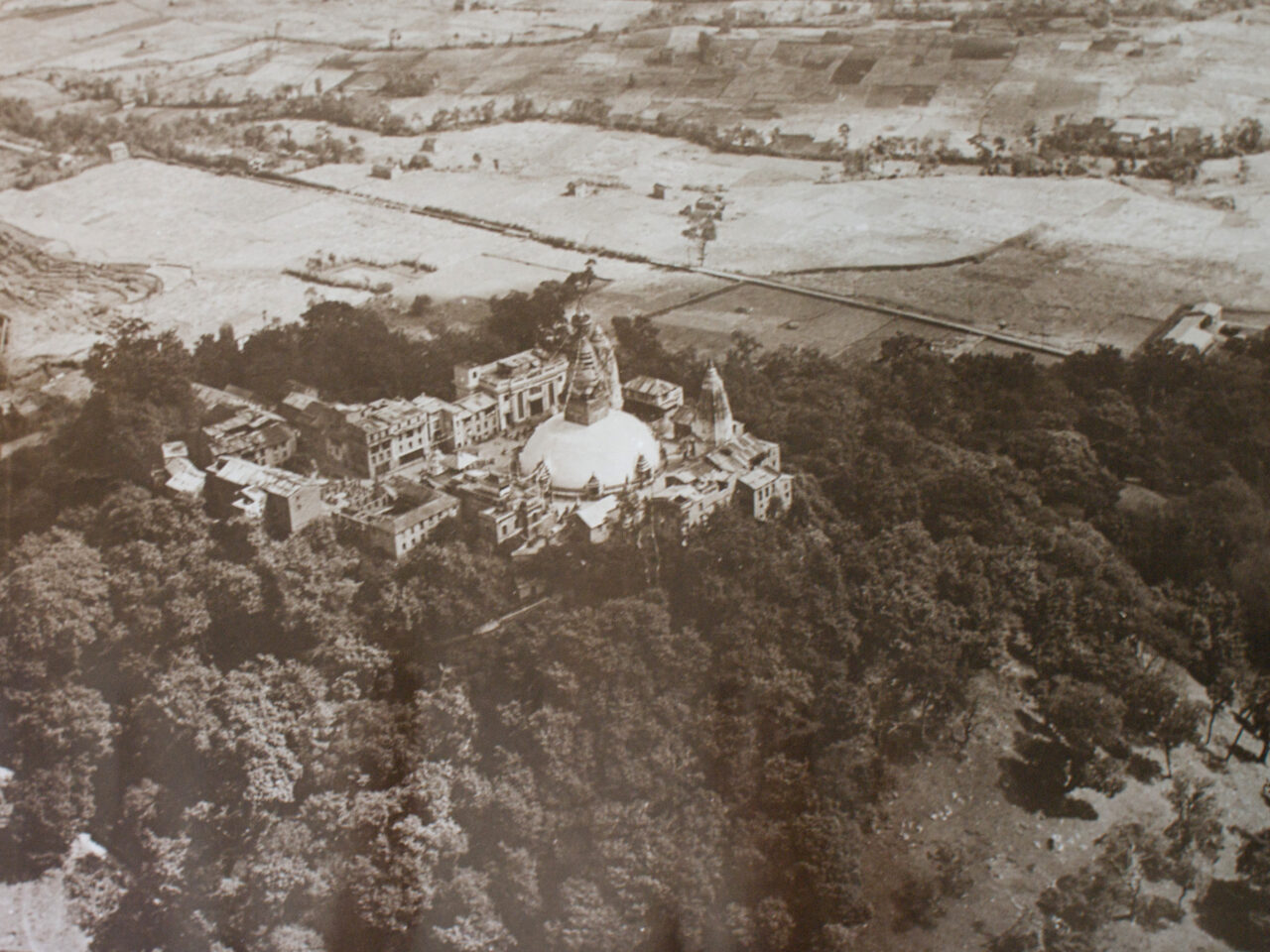

Himalayan kingdoms of the Kathmandu Valley were major centers of Buddhist culture, becoming especially significant with the decline of Buddhism in India and Kashmir. Tibetan Buddhists went to Nepal in search of teachers and instruction in tantric practices, as many Indian scholars moved to Nepal where Buddhism remained a thriving tradition. Nepalese kings, Buddhist institutions (bahas), and ordinary people patronized the vibrant art guilds. The arts of the Kathmandu valley were well-known in Tibetan areas and beyond and artists have always been in high demand throughout Tibetan regions and Inner Asia for their skill and their willingness to travel. In Nepal, Hindu and Buddhist cultures coexist. Nepalese kings sponsored Hindu and Buddhist religious sites, and the same artists often produced images for both communities, creating a shared visual culture that continues today.

The northwestern face of the Svayambhu chaitya, Kathmandu, Nepal, with the niches of the Buddha Amoghasiddhi in the north, Amitabha in the west, and the goddess Aryatara in between, 2002; photograph by Manika Bajracharya, Lotus Research Centre, Lalitpur

Spout of Golden Fountain of Bhaktapur Palace; Bhaktapur, Nepal; 1688; stone, repoussé metalwork; dimensions unknown; photograph by Christian Luczanits, 2010

Deshay Maru Jhya (Window without an Equal); Yetakha tol; Kathmandu, Nepal; ca. 18th century; wood; photograph by Sameer Tuladhar, 2021

Procession of Bunga Dya's chariot through Patan. Rohit Maharjan, "Rato Machindranath Jatra | MangalBazar to Sundhara | Patan, Lalitpur | 2079," YouTube, May 8, 2022, 15:02, https://youtube.com/p2LhXrlpGgQ.

Bhutanese Regions Permalink

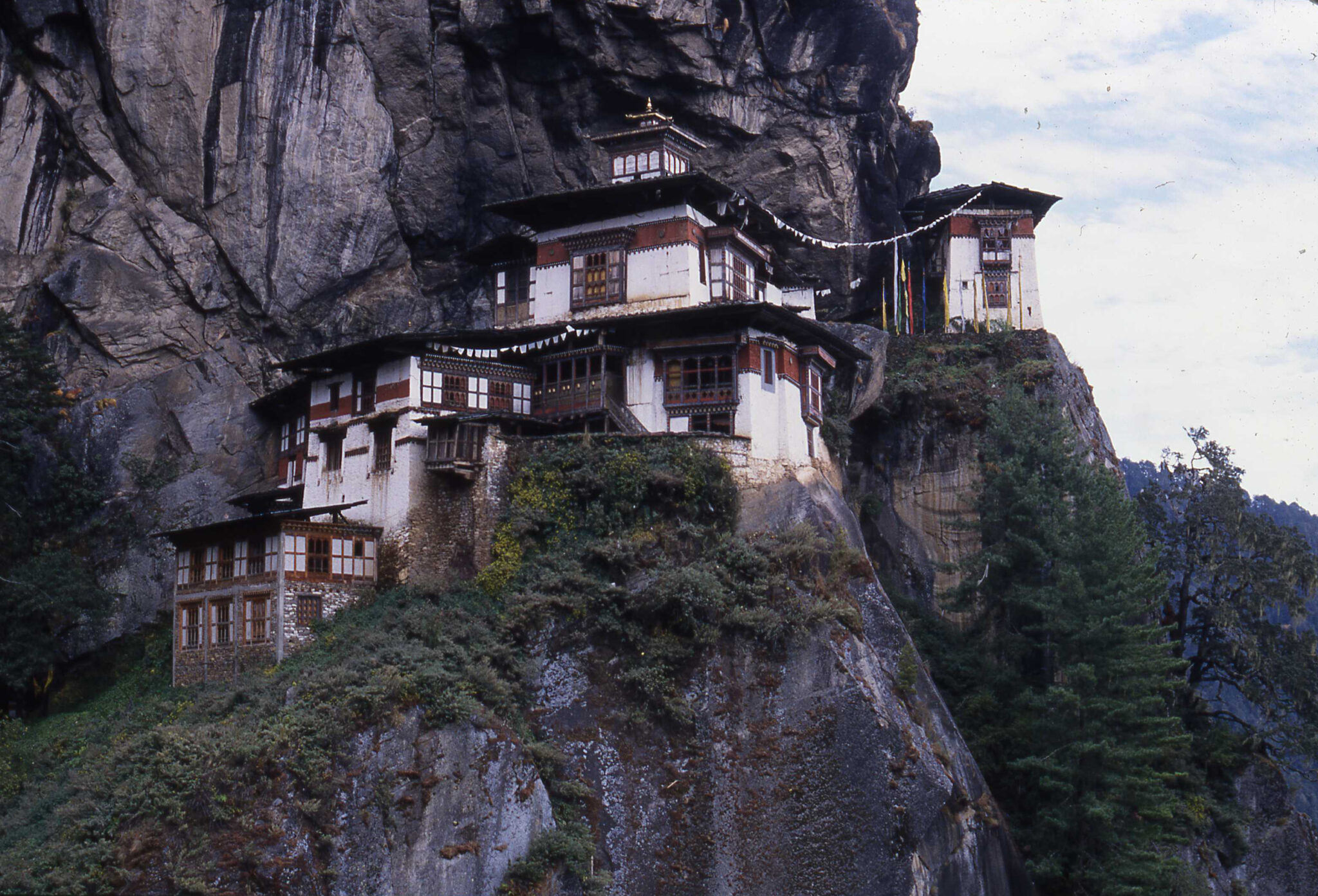

The earliest Buddhist temples in what is now the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan are said to have been built around the same time was introduced in Tibet during the seventh century. Close ties between Bhutan and Ladakh were fostered through common Kagyu Buddhist transmission lineages and monasteries, in central . In the early 17th century, under pressure from Mongol-backed power in Tibet, many teachers moved to Bhutan where they had supporters. By the mid-17th century, Shabdrung Rinpoche (1594–1651) unified Bhutan under his religious and temporal authority and established a government. Although this unity did not last, the overall identity of Bhutan has endured and continued under the rule of various regional local powers.

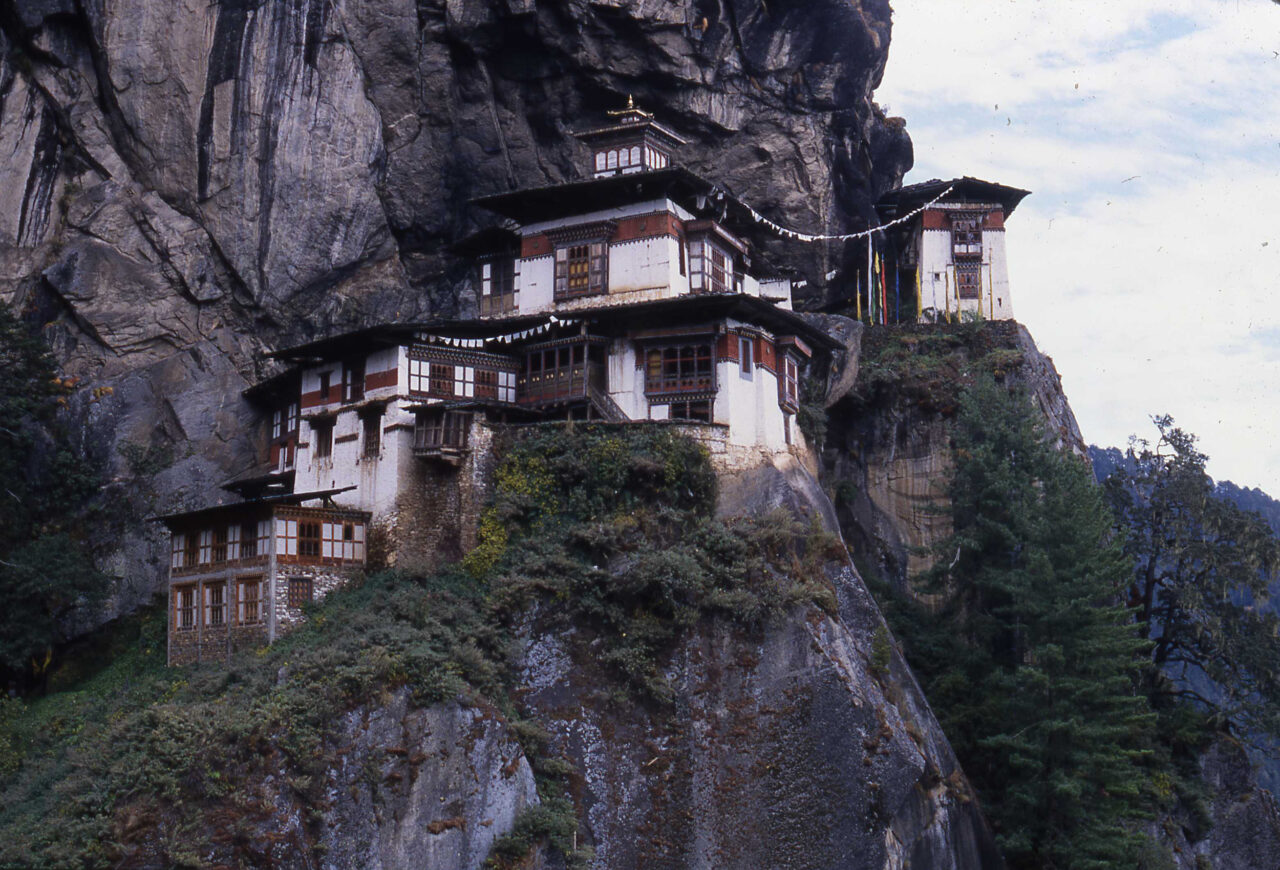

Taktsang Lhakhang; Upper Paro Valley, western Bhutan; constructed 1692–1694 by command of Desi Tenzin Rabgye (1638–1696); photograph ©John A. Ardussi, 1995

Giant appliqué scroll representing Padmasambhava and his Eight Emanations; Paro Tshechu, Bhutan; photograph © F. Pommaret, March 2017

Tamshing Lhundrub Choling Temple; Bumthang District, Bhutan; founded 1501, consecrated 1505; photograph by Ariana Maki

For a glimpse of life in Bhutan in the 1970s and 1980s see the film by Marie-Noëlle Frei-Pont. Reproduced with permission. Travel with Claudio, "Country Life in the Bumthang Valley Bhutan 1974 – 1982," YouTube, February 20, 2023, 1:22:14, https://youtu.be/K3Bjr8K_DEw.

Central Asian Regions Permalink

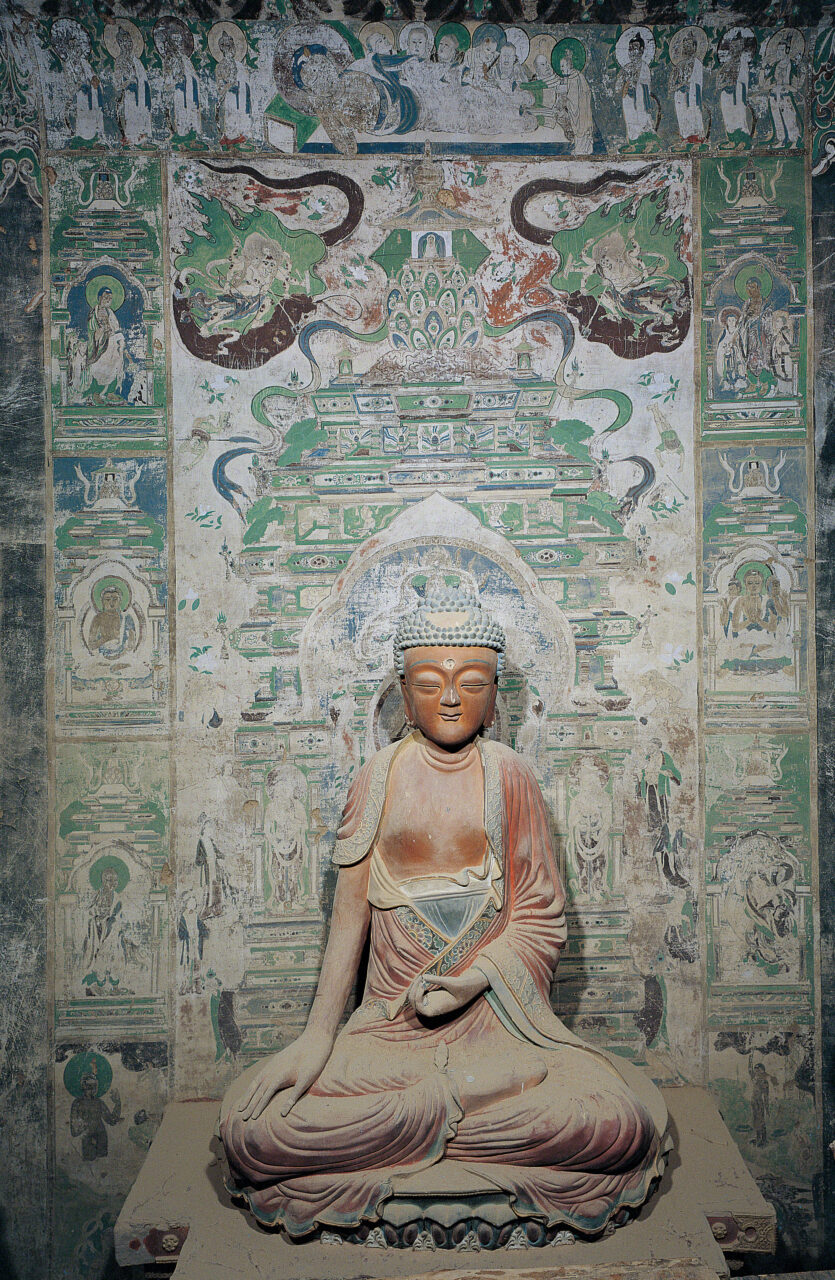

Traveling merchants, monks, pilgrims, locals, and even armies of various empires met and mixed at the Central Asian oasis centers along the trade routes that connected Asia with the West. They were among the donors, visitors, and artists who created and contributed to the famous caves located at the eastern juncture of the trade routes of the so-called “” trade networks.

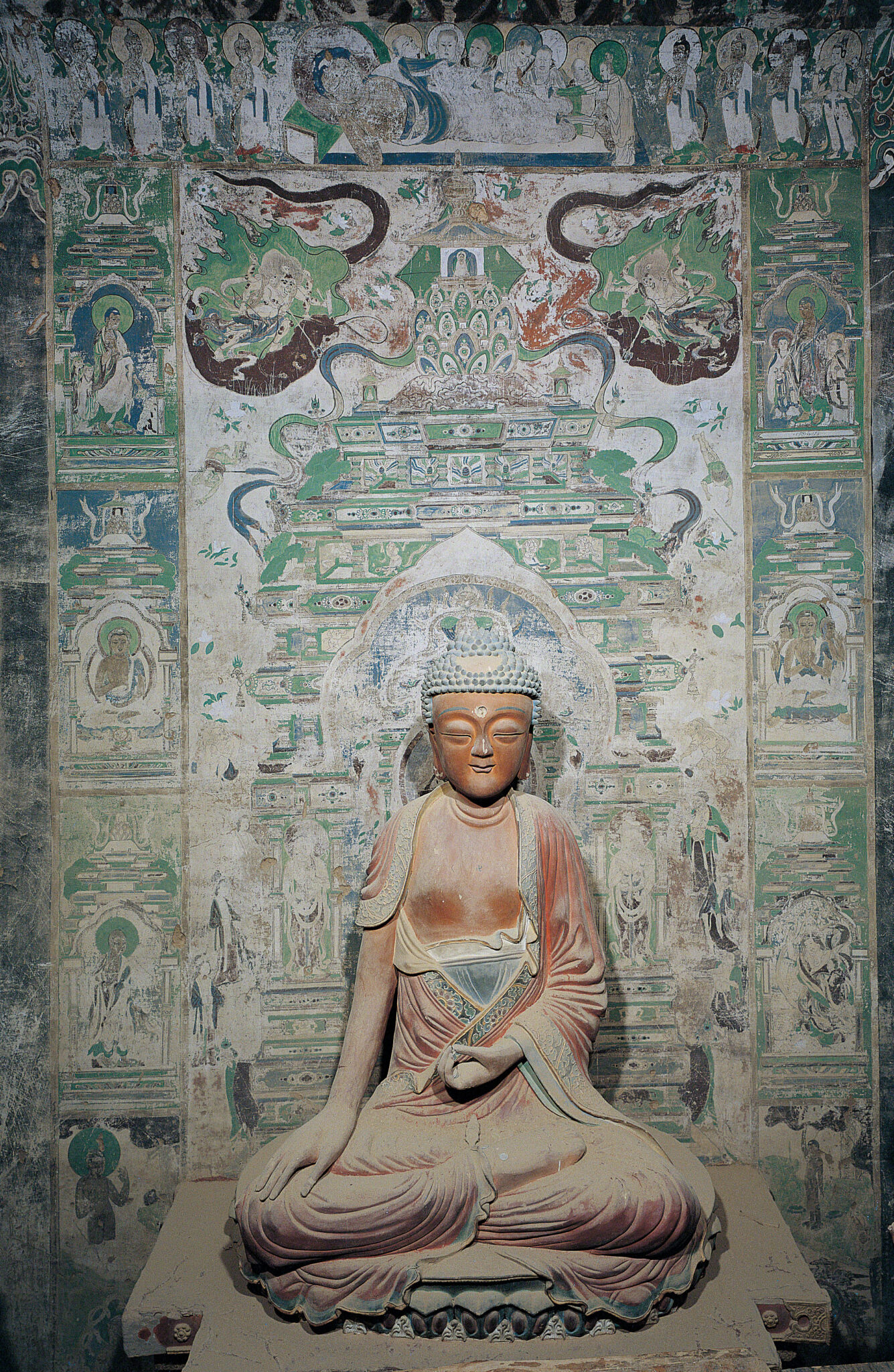

The diverse visual traditions, belief systems, and languages found in murals, statues, and texts testify to these rich cross-regional and cultural connections. Tibetans were among the powers who ruled the area during the height of the , and their presence is documented in the material culture of Dunhuang. formed a cosmopolitan state known as Xixia that had a significant impact on the artistic production in the area and on Tibetan and Inner Asian religious culture, especially the Mongol Empire.

Yulin Cave 3, East Wall center, Eight Pagodas, Tangut Kingdom (Xixia), (present-day Anxi, Gansu Province, China); ca. late 12th century; image courtesy Dunhuang Research Academy, photograph by Wu Jian

Paradise of Bhaishajyaguru; Dunhuang, China; 836; ink and color on silk; 60 × 70 in. (152.3 × 177.8 cm); The British Museum, London; 1919,0101,0.32; photograph © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved

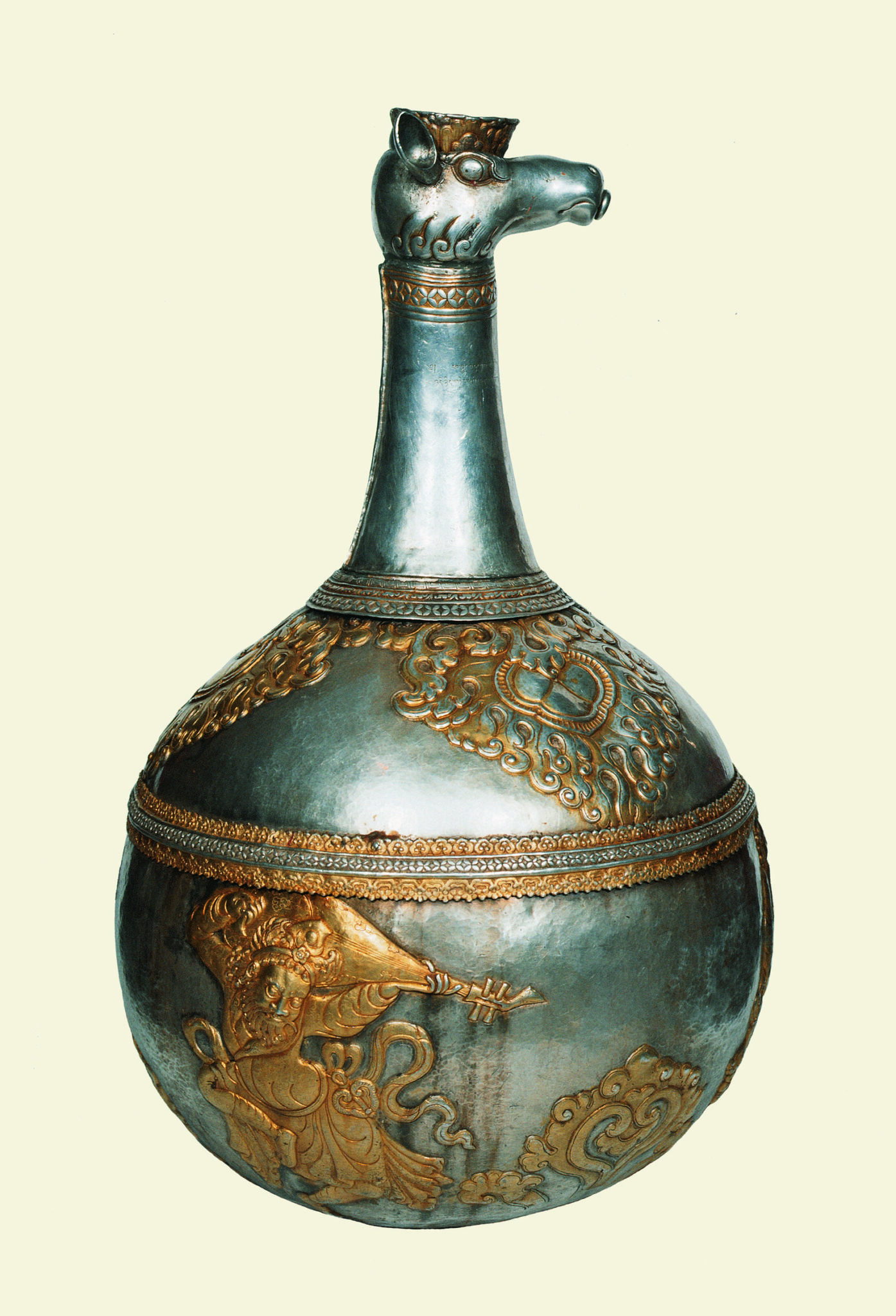

Silver Jug, Tibet, 9th–10th century, based on earlier Sogdian or Uyghur prototypes; hammered silver with gilding; height approx. 31 1/2 in. (80 cm); Jokhang temple, Lhasa; image after von Schroeder 2001, 793, fig. 190A

Mongolian Regions Permalink

Mongolians have been widely active in the political, religious, and artistic life of the Tibetan Buddhist world, particularly the western Mongols, or Zunghar (now in Xinjiang Province) and eastern Khalkha Mongols (in the current State of , the various tribes in modern-day Inner , as well as Buryat and Kalmyk Mongols in areas that are now a part of Russia.

In the 13th century, the Mongols built the largest contiguous empire in world history, conquering most of Asia and facilitated the spread of Tibetan visual culture in eastern Asia. They established communication systems across the empire, including courier relay systems that connected cultural centers, moving people, objects, and ideas across the diverse cultural regions. Under Mongol rule, skilled artisans were sought from all over the empire, and the head of the Yuan imperial atelier was a Nepalese artist. Mongols played a key role in Tibetan culture and politics and Tibetan relations with China. In fact, Mongolian was often the common language among these cultures.

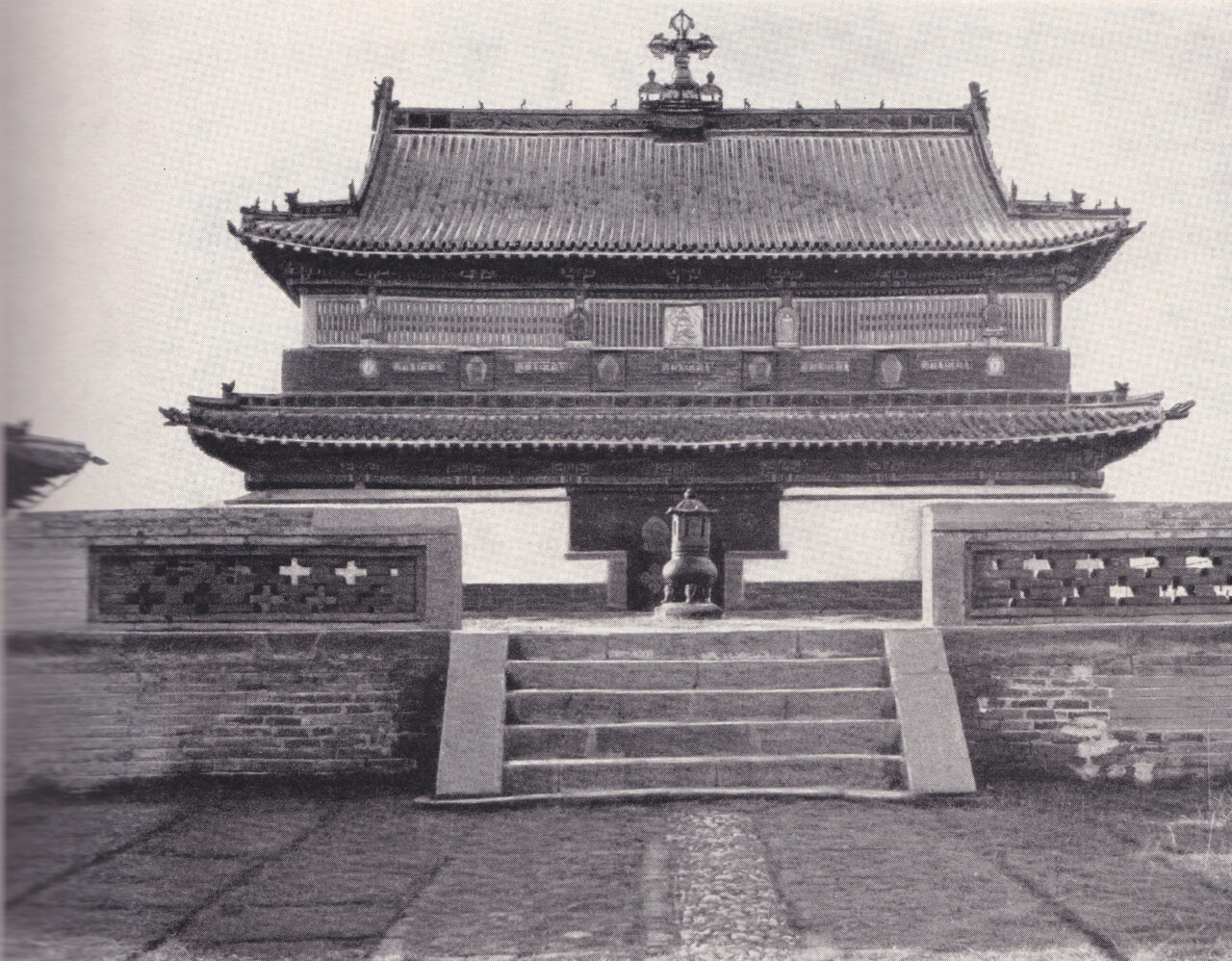

The Central Temple of Erdeni Juu Monastery, founded by Abatai Khan; Övörkhangai Province, Mongolia; 1586–1587; floor dimensions 48 ft. 9 in. × 37 ft. 3 in. (14.85 × 11.35 m); early 20th-century photograph; image after Maidar 1972, fig. 75

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Capital Yekhe Khüriye; Mongolia; 1912; colors on cotton, 19-5/8 × 37-7/8 in. (50 × 96 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Kalachakra (Dechingalba) Temple in Yekhe Khüriye Monastery; late 19th century; photograph National Central Archives of Mongolia

Chinese Regions Permalink

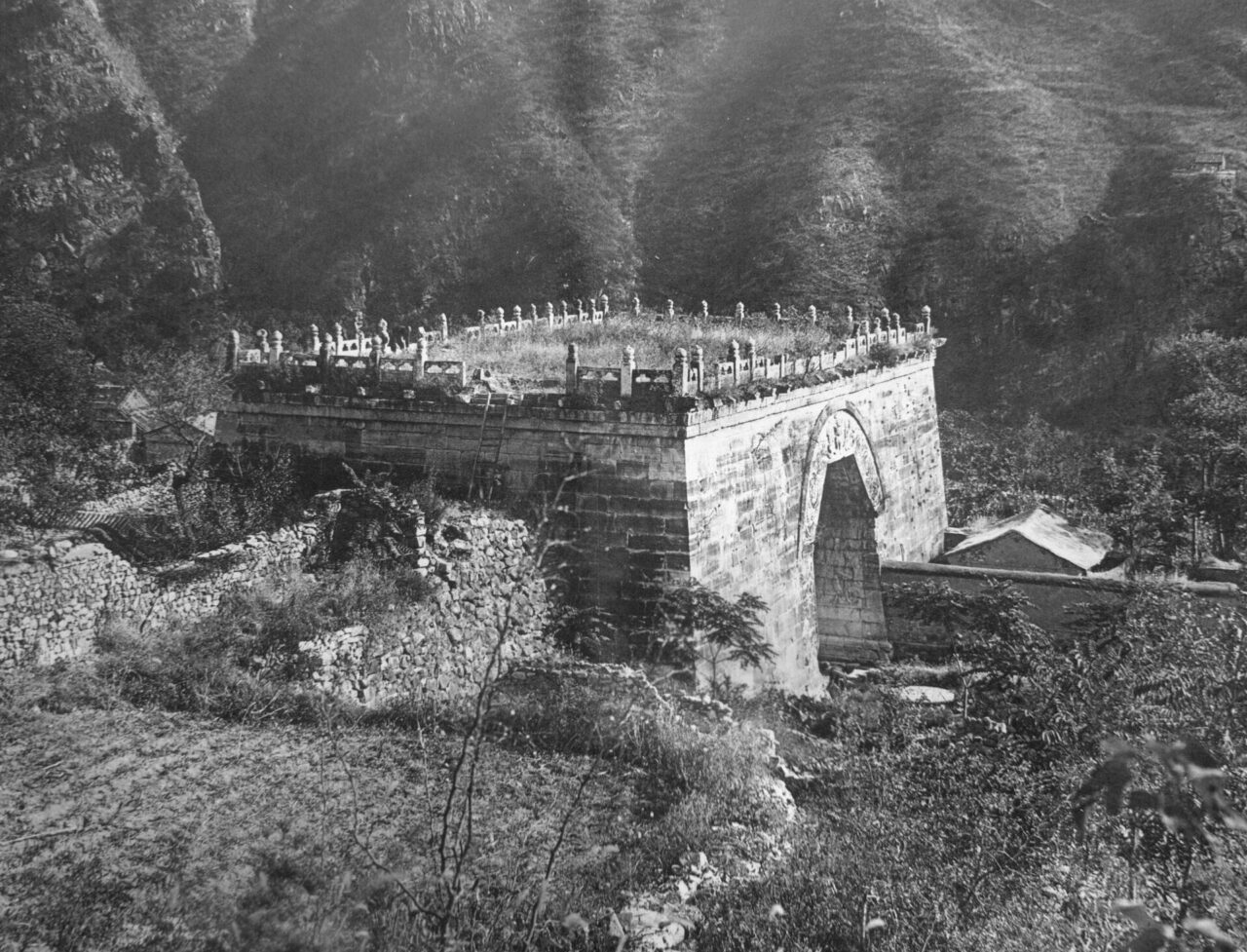

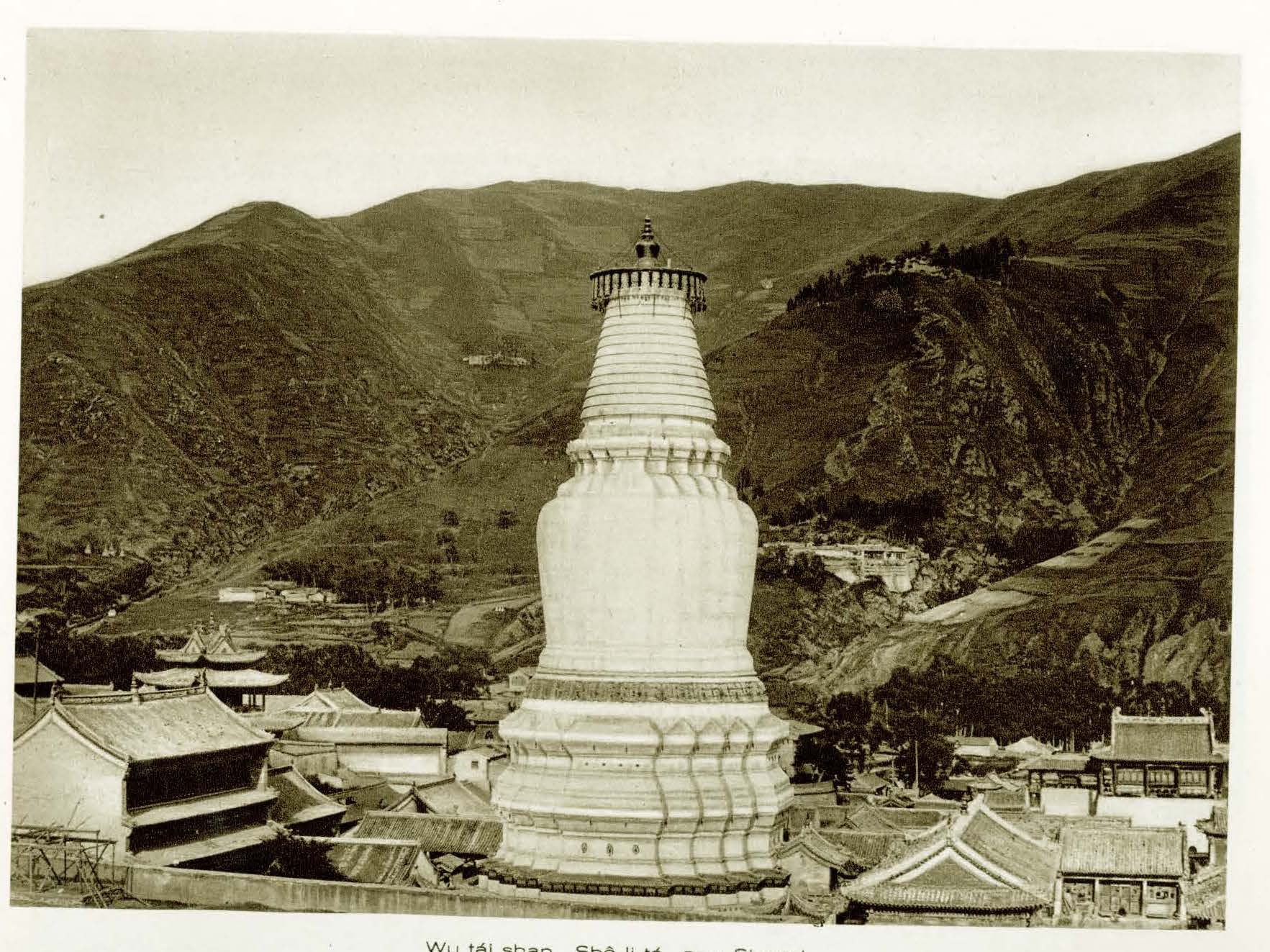

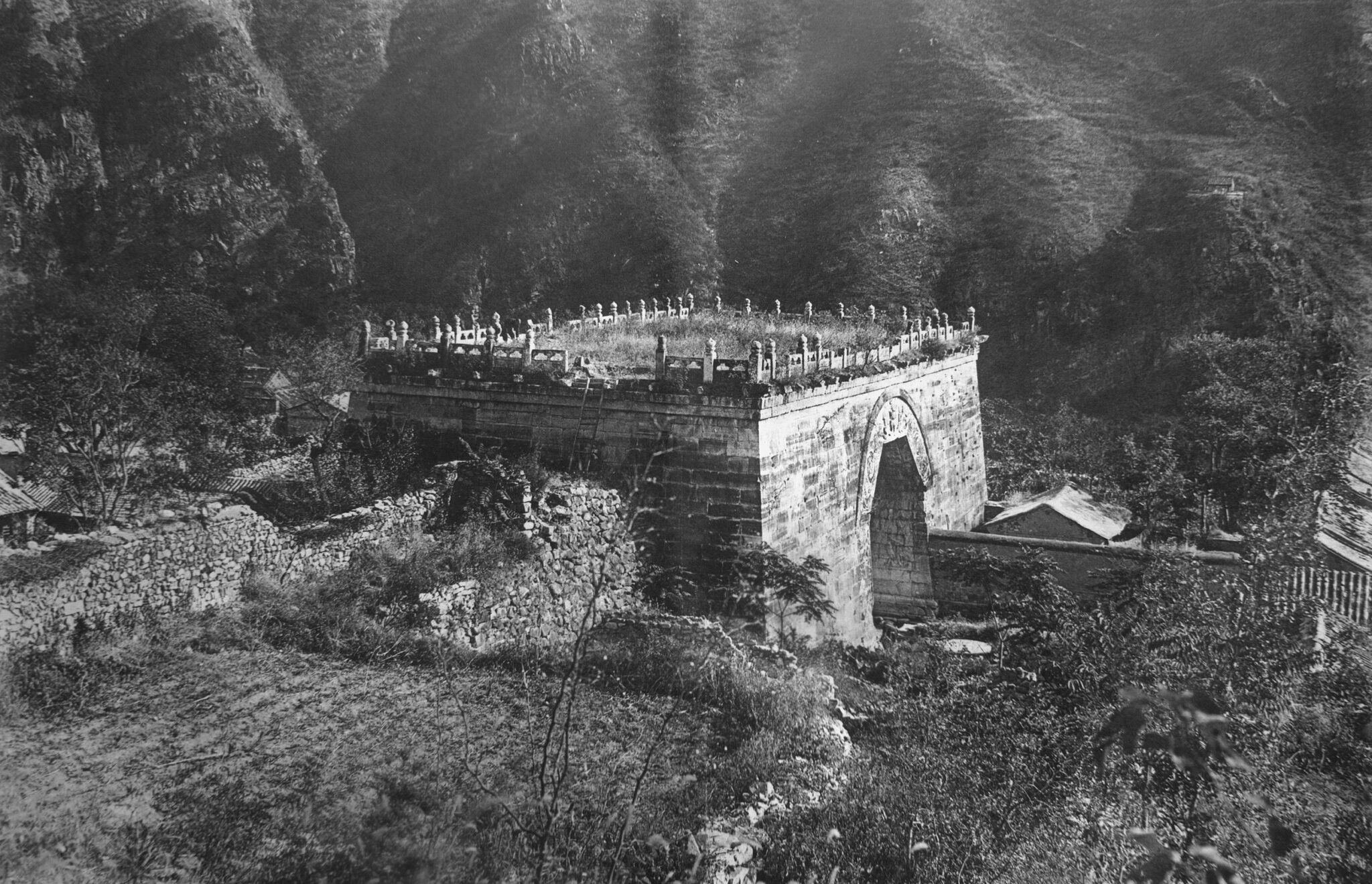

Emperors of the Mongol Yuan (1270–1368), Chinese Ming (1368–1644), and Manchu Qing (1644–1911) embraced culture and used Buddhist ideas to support their rule over the multiethnic populace in their domain and declare their legitimacy to neighboring regions. Although Tibetan Buddhism was not practiced broadly among the Chinese people, the imperial centers, such as and Wutaishan, became centers of Tibetan Buddhist cultural production. Tibetan Buddhist monuments engraved into the landscape signified imperial , and lavish images were produced for use within the courts and as gifts to Tibetans, Mongolians, and other Inner Asian neighbors.

White Stupa, known as Precious Stupa of Great Compassion and Longevity and its surroundings, photographed between 1906 and 1909; Great Precious Stupa Cloister Monastery; Mount Wutai, Shanxi Province, China; 1301, renovated in 1407; height after the 1407 restoration 185 ft. (56.4 m); image after Boerschmann, Ernst. 1923. Picturesque China: Architecture and Landscape: A Journey through Twelve Provinces. New York: Brentano’s

Juyong Guan Stupa Gate; Nankou Town, Changping District, Beijing, China; dated 1345; white limestone; 32 ft. 9 1/2 in. × 88 ft. 7 in. × 59 ft. (10 × 27 × 18 m), gateway: 23 × 59 ft. (7 × 18 m); image after Murata 1958, pl. 1

Monk Lhundrub, engraver of Sanggai Aimag (Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia); Panoramic Map of Mount Wutai; Cifu Temple, Mount Wutai, China; 1846; woodblock print on linen, hand colored; 47 1/8 × 68 in. (119.7 × 172.7 cm); Rubin Museum of Art, Gift of Deborah Ashencaen; C2004.29.1 (HAR 65371)

Object Essays About Prominent Locations Permalink

Glossary Terms Permalink

Bodhgaya is the site where the historical Buddha Shakyamuni is said to have attained enlightenment. Located in what is now the Indian state of Bihar, Bodhgaya is the site of the Bodhi Tree, the “diamond throne” (vajrasana), and the Mahabodhi Temple. Bodhgaya is arguably the most important pilgrimage site for Buddhists.

Kathmandu Mandala is a term used to describe the political and religious landscape of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal, traditionally inhabited by Newar people. Politically, the Kathmandu Mandala consisted of the three city-states of Kathmandu, Bakhtapur, and Patan, as well as smaller settlements around them. Religiously, the Kathmandu Mandala was a network of Hindu and Buddhist sacred sites that marked the center and boundaries of the region. From 1768 the Kathmandu Valley was unified under the rule of the Shah dynasty from outside of the valley.

Newar

The Newars are traditional inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. The Newars speak a Tibeto-Burman language (Newari) and practice both Hinduism and Buddhism. The Newars are inheritors of one of the oldest and most sophisticated urban civilizations of the Himalayas, and Newar arts and artisans have been celebrated all across the Himalayan world since the Licchavi period.

Tibetan people

Tibetans are an ethnic group who live on the Tibetan plateau, as well as neighboring parts of northern India, Nepal, and around the world. Traditionally, Tibetans have combined agriculture in the river valleys with pastoral animal husbandry on high plateaus. Most Tibetans are Buddhists, but there are also followers of Bon, Islam, and other indigenous ritual traditions. Today, there are about seven million Tibetan people globally.

Tibetan Empire

In the early seventh century, a line of kings from the Yarlung Valley united disparate people on the Tibetan Plateau into a powerful, centralized state. With their capital at Lhasa, these kings proclaimed themselves emperors, or tsenpo. Their armies conquered much of the Himalayas, Central Asia, and western China. Tibetans developed a written script for the Tibetan language and Buddhism was adopted as a state religion. The conversion to Buddhism was contested by an indigenous group of ritualists called Bon, creating political turmoil. After the assassination of emperor Langdarma in 842, the Tibetan empire fragmented and collapsed. Nevertheless, the myths and memories of the empire continue to be a central part of Tibetan identity.

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire (ca 1206–1368) was the largest contiguous empire in world history, founded by Chinggis Khan (1162–1227), which at its height controlled most of Eurasia, from the Korean peninsula to Central Europe. The Mongols conquered the Tanguts in 1227 and absorbed Tibetan regions in the 1240s, granting power over central Tibet to the Sakya Buddhist hierarchs in what is characterized as a priest-patron relationship. In 1260, Qubilai Khan declared himself Great Khan, which was contested, fracturing the Mongol Empire into four independent regimes. Qubilai remained the ruler of most of Asia establishing the Yuan dynasty. Mongol rulers of Yuan, and the first six rulers the Ilkhanate in the Middle East, starting with its founder Hülegü, were also patrons of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Khalkha are one of the major historical subgroupings of the Mongols. Historically ruled by leaders descended from Chinggis Khan, the Khalkha inhabited a territory roughly the same as the country called Mongolia today. Other important Mongol groups after the fall of the Mongol Empire include the Chahars, who lived in what is today the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in China, the Oirat or Dzungars, who lived in Central Asia, and the Khoshut, who lived in the northern Tibetan Plateau.

The Oirats are a major western branch of the Mongol people, dating from at least the time of Chinggis Khan (1162–1227 CE). The Oirats have several historically important sub-branches. The leader of Khoshud branch, Güüshi Khan (1582–1655), allied with Gelukpa monasteries and occupied Tibet in the 1630s–40s, and was named king. Together, they established the Ganden Podrang government in Lhasa with Dalai Lamas at its head. The Zunghar branch established a state in eastern Central Asia in the early seventeenth century, and played a significant role in the political and religious affairs of the eastern Khalkha Mongols, as well as Tibet in 1717–20. The Kalmyk branch, which migrated to what is now southwestern Russia in 1607–30, are the only majority-Buddhist ethnic group on the European continent.

Silk Roads

“Silk Roads” is a term broadly used to describe the long-distance trade routes across Central Asia that connected the Indian Subcontinent with East Asia and the Mediterranean world. These trade routes were highly important in transmitting both art and ideas across the Asian continent, including the Buddhist religion. There were many “silk roads”—some crossed the deserts of Central Asia, other maritime routes also connected Europe, the Middle East, Africa, South, Southeast, and East Asia.

The Tanguts were an ethnic group in medieval East-Central Asia, who called themselves Minyak and spoke a language distantly related to Tibetan. Between 1038 and 1227 CE the Tanguts ruled a state in what is now the Chinese provinces of Ningxia, Gansu, and Qinghai. This state took the Chinese dynastic name of Xia, also called Xixia “Western Xia.” The Tangut-Xixia emperors were major patrons of Buddhism, inviting both Chinese and Tibetan monks to teach in the capital, and instituting major Buddhist translation and printing projects in three languages. The Tangut state was destroyed by the armies of Chinggis Khan, leading to their absorption into the Mongol Empire, where many Tanguts served as officials.

Sogdians

The Sogdians were a historic Central Asian people who originated in the region of present-day western Tajikistan and surrounding areas of Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. The Sogdians spoke a language related to Persian and were major players in the medieval Central Asian caravan trade, forming crucial contacts between Persia, China, and Tibet. They were important conduits of artistic traditions and material culture, including Sasanian metalwork and Central Asian silk weaving. After the Arab conquest of their homeland in the eighth century, the Sogdians mostly disappeared from history, although the Sogdian language is still spoken by a few thousand people in the mountains of Tajikistan.

The Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) is the branch of the Mongol Empire in Asia. In 1260 when Qubilai Khan declared himself Great Khan, his realm included Mongolian, Chinese, Tangut, and Tibetan regions. In 1271 emperor Qubilai Khan proclaimed the Yuan dynasty on a Chinese model, employing Tibetan and Tangut monks. Tibetan Buddhism played an important role in the state, establishing a political model that would be emulated by later dynasties, including the Chinese Ming and Manchu Qing dynasties. The Mongols were major patrons of Tibetan institutions, and many Mongols converted to Tibetan Buddhism, though their interest declined with the fall of the empire.

Ming Dynasty

The Ming dynasty was a Chinese state that existed from 1368 to 1644 CE. The Ming founder, Zhu Yuanzhang (1328–1398), led an army that defeated the Yuan dynasty of the Mongol Empire and restored ethnic Chinese rule in China. Unlike the Mongols before them or the Qing dynasty after them the Ming never seriously attempted to rule the Tibetan regions, preferring instead to manage border affairs by granting titles and trading rights to friendly Tibetan monks and secular leaders. Nevertheless, several early Ming emperors had close personal relations with Tibetan lamas, and relations of trade and cultural interchange flourished between Chinese and Tibetan regions.

The Qing dynasty was a state that ruled in Eastern Asia from 1636 to 1912. Founded by the Manchus in 1644, the Qing armies crossed the Great Wall and began their conquest of the rest of the Chinese cultural region. By the 1750s the Qing empire had expanded to rule all of Mongolia, Tibet, and eastern Central Asia (including today’s Xinjiang), laying the groundwork for the modern state of China. The Qing governed Tibet and parts of Mongolia indirectly, in which the Manchu armies provided military support for local Buddhist governments like the Ganden Podrang. Tibetan and Mongol lamas were also extremely important in Qing court culture, and had close relationships with several Qing emperors.

The Gupta empire was a state centered in northeastern India. The Gupta empire expanded from the fourth century CE to control much of central India and the Ganges valley regions, receiving tributes from other rulers as well. Under the strain of military invasions from the northwest, the empire declined in the late sixth century. The Gupta period is considered a classical age of Hindu and Buddhist art and culture, which produced many of India’s greatest philosophers, playwrights, and artists. Elite patronage of Buddhist institutions was also a major feature of the age, and sculpted Buddhist images are among the most famous and representative images of that time.

Malla Dynasty

The Malla dynasty ruled the Kathmandu Valley in central Nepal from the early thirteenth century until 1769. For most of this period, there was not one single Malla ruler; rather, different branches of the Malla family formed a Newar-speaking noble class that ruled the three city-states of Kathmandu, Bakhtapur, and Patan. Due to the cultural competition between these cities and courts, the Malla period is remembered as a great age of Hindu and Buddhist art and architecture in Nepal. The Malla period came to an end when the Gorkha ruler Prithvi Narayan Shah (1723–1775) conquered the area of present-day Nepal. (The Malla dynasty is not to be confused with the Khasa Malla.)

Inner Asia

Inner Asia is a broad geographic term referring to diverse Mongolian regions including present-day Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, Buryatia, Tuva, and ancient territories traditionally occupied by Tangut and Manchu people, as well as areas of Western China. In some contexts Tibetan regions are also considered part of Inner Asia.