Summary

Why did an Italian Jesuit paint the portrait of an emperor on the body of the bodhisattva Manjushri? The emperors of the Qing dynasty ruled a vast multiethnic empire that encompassed Manchus, Chinese, Mongols, and Tibetans, and even employed European specialists at court. Art historian Wen-shing Chou examines how the Qianlong emperor created the unprecedented visual articulations of religious kingship to project himself and the Manchu imperial line as divine bodhisattva rulers at the center of the Buddhist cosmos.

Key Terms

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

The Geluk are the most recent of the major “Later Diffusion” traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Founded on the teachings of Tsongkhapa (1357–1419 CE) and his students, the Geluk are known for their emphasis on monastic discipline and the scholastic study of Mahayana philosophy, especially Madhyamaka. In the seventeenth century the Geluk supporting the Dalai Lamas became the largest and most powerful Buddhist tradition in both Tibet and Mongolia, where city-sized Geluk monasteries and their satellites proliferated widely. For long periods, Geluk monks effectively ruled both countries in dual-rulership or priest-patron political systems. A follower of the Geluk is called a Gelukpa.

iconography

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

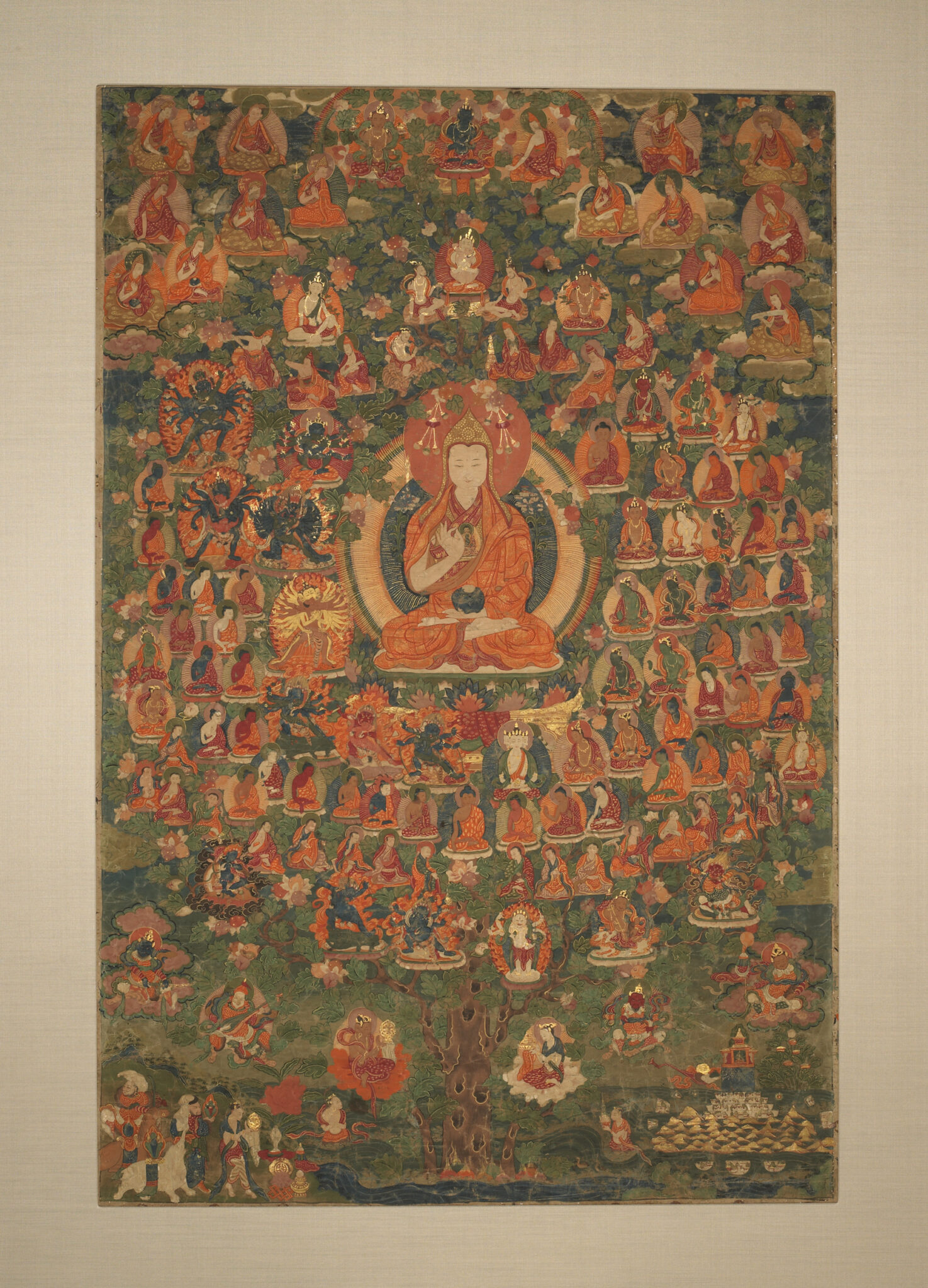

refuge field

Becoming a Buddhist is often described as “taking refuge” in the Three Jewels: the Buddha, the Dharma (teachings), and the Sangha (monastic community). A “refuge field” or “tree of refuge” is a particular genre of Tibetan painting that depicts all the important deities and historical masters of a particular Buddhist tradition in a tree-like arrangement. It shows an assembly of gurus and deities as they should be imagined when a meditator mentally takes refuge in them. These images often systematize the transmission lineage, or the uninterrupted line of teachers through which knowledge and tantric initiations and instructions were passed down, stretching back to the Buddha himself.

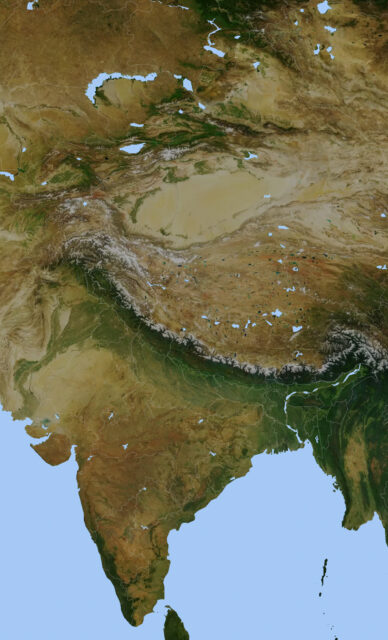

Manchus are an ethnic group originating in northeast Asia, roughly the area known as Manchuria. Historically known as Jurchens, in 1635 the ruler Hong Taiji (1592–1643) proclaimed the Qing Dynasty and officially changed the ethnic group’s name to “Manchu.” Qing emperors were said to be emanations of the bodhisattva Manjushri, and the name “Manchu” may relate to this. The Manchus formed the military aristocracy of this empire, which came to rule most of China, Mongolia, Tibet, and Eastern Central Asia until 1912. Many Manchus, including Qing emperors, had close political and spiritual relationships with Tibetan and Mongol lamas. Today the Manchus remain a major ethnic group within China, although very few people now speak the Manchu language.

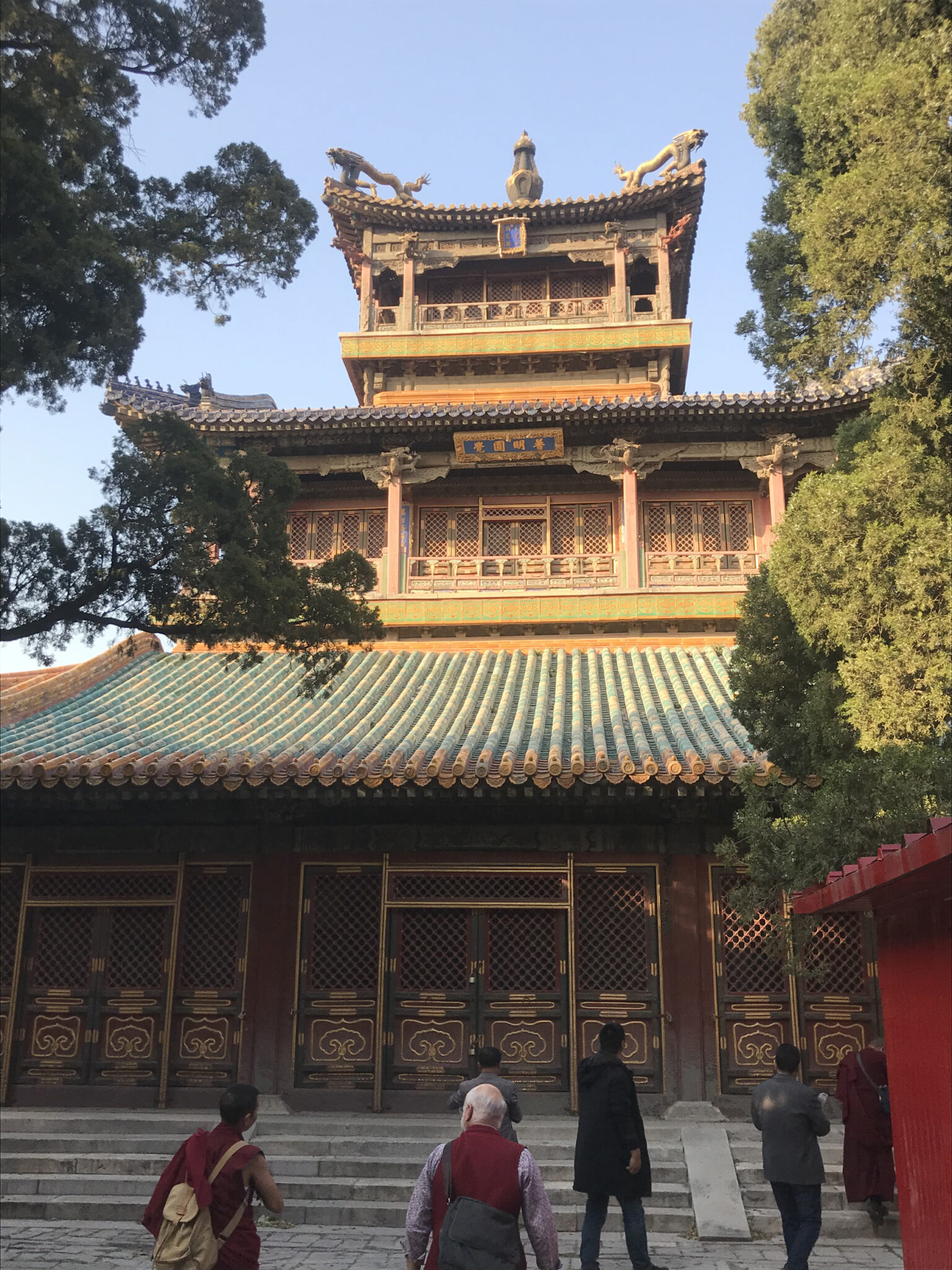

The Qing dynasty was a state that ruled in Eastern Asia from 1636 to 1912. Founded by the Manchus in 1644, the Qing armies crossed the Great Wall and began their conquest of the rest of the Chinese cultural region. By the 1750s the Qing empire had expanded to rule all of Mongolia, Tibet, and eastern Central Asia (including today’s Xinjiang), laying the groundwork for the modern state of China. The Qing governed Tibet and parts of Mongolia indirectly, in which the Manchu armies provided military support for local Buddhist governments like the Ganden Podrang. Tibetan and Mongol lamas were also extremely important in Qing court culture, and had close relationships with several Qing emperors.

Manjushri is one of the most important bodhisattvas in Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Considered the embodiment of wisdom, Manjushri is often recognized by his attributes: a sword which cuts through ignorance and a book, the Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) Sutra. Emanations of Manjushri can also be recognized by these same attributes. Another important Chinese iconographic tradition depicts a youthful Manjushri riding on a lion. This form is associated with Manjushri’s abode on earth, Mount Wutai in China, one of the few Buddhist sites in China visited by Tibetan and Mongol pilgrims among others from all over Asia. Manjushri was seen as the protector deity of China, and the Manchu emperors of the Qing Dynasty who claimed to be emanations of Manjushri emphasized/promoted this association.

A chakravartin is an ideal of Buddhist kingship, a universal ruler who supports the sangha and “turns the wheel of the Dharma.” Since the time of Emperor Ashoka (304–232 BCE), the archetypal chakravartin, many Buddhist rulers in history have been praised as chakravartins, or rulers who support Buddhism and help its spread through the expansion of his domains.