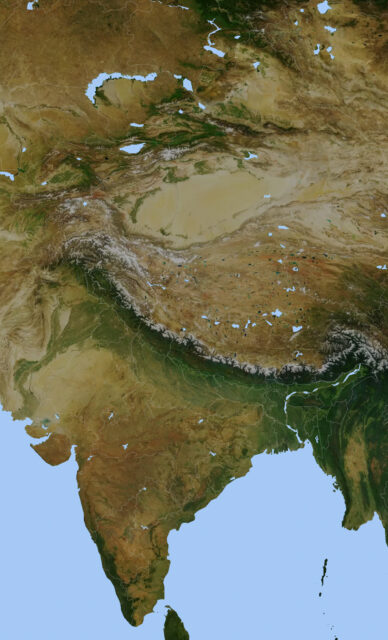

Art making in Himalayan and Tibetan regions is largely religious in nature. The making of these religious images, both two- and three-dimensional, is guided by or rules of outlined in text and passed down from a master artist to students, and sometimes preserved in manuals and sketchbooks. Individuals, families, communities, as well as commission artworks for religious and secular purposes, such as rituals, communal festivals, personal life events, and to accumulate religious .

Two-dimensional Images Permalink

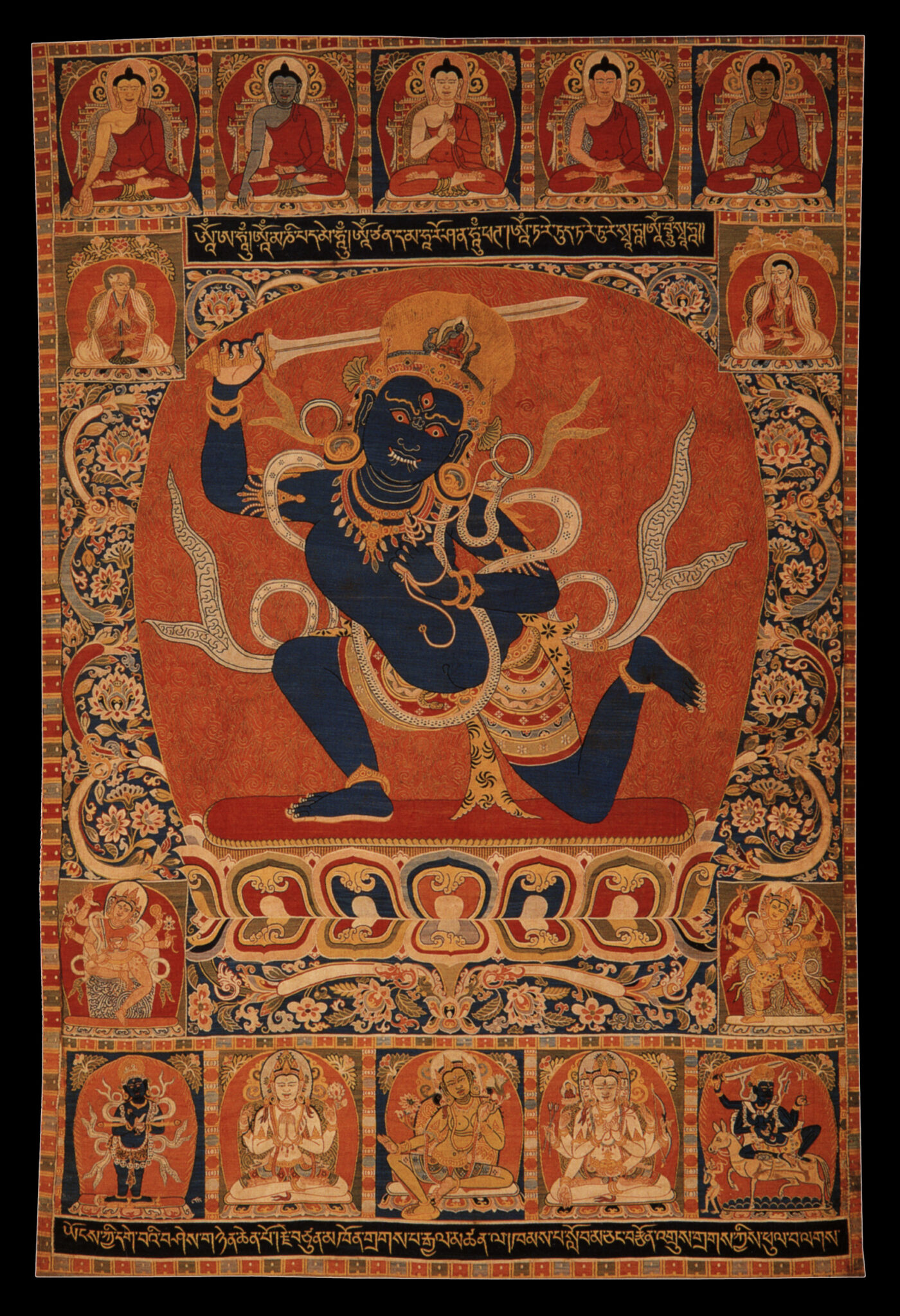

Painting

Painting is the primary artform of two-dimensional images, and includes hanging scrolls painted on (Tibetan ; Newari ), large-scale murals on the walls of temples and monasteries, and miniature illuminations within the pages of decorated . The process of Tibetan thangka painting is demonstrated and described in detail in the exhibition theme: painting.

The Rubin Museum of Art, "The Making of a Thangka Painting," YouTube, January 23, 2023, 6:55, https://youtube.com/watch?v=ykteMInqG7w.

Printing and Paper Making

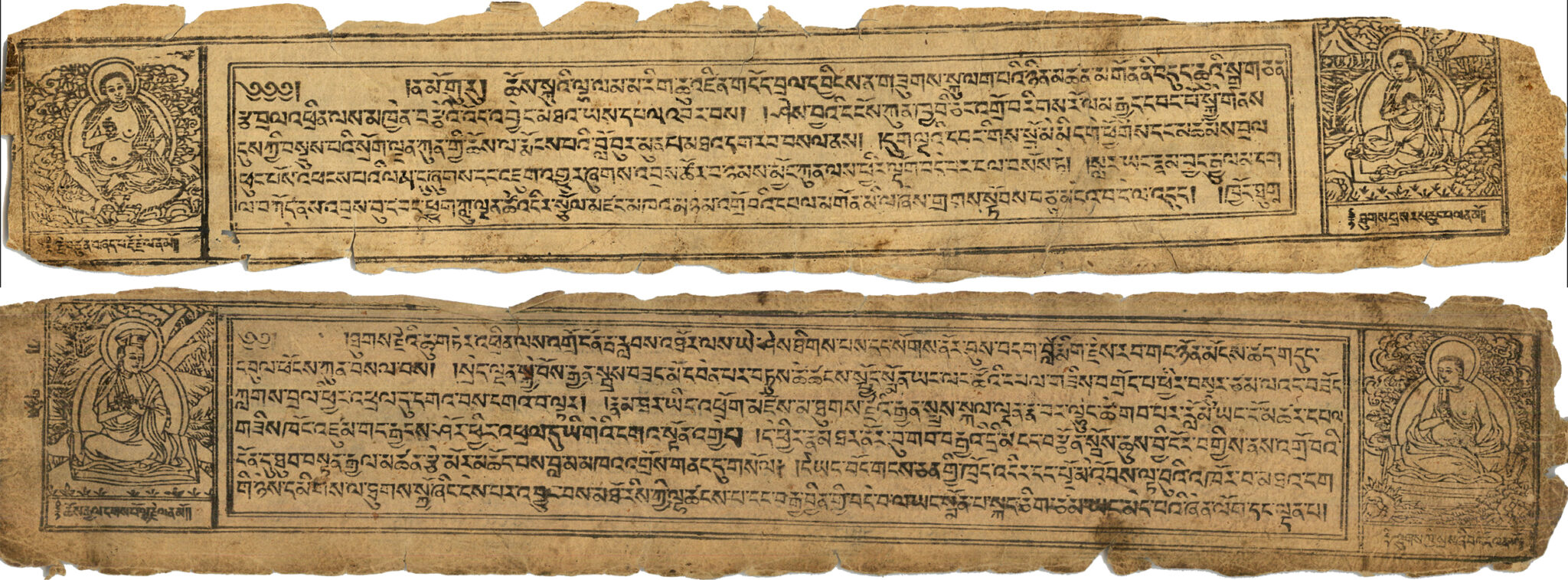

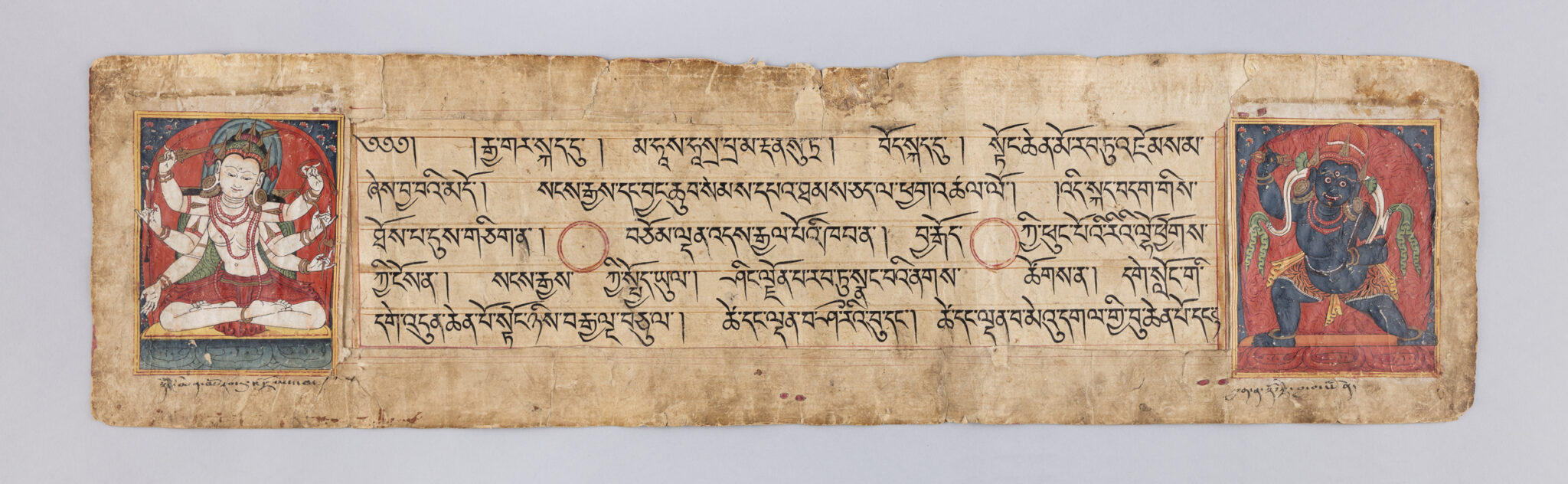

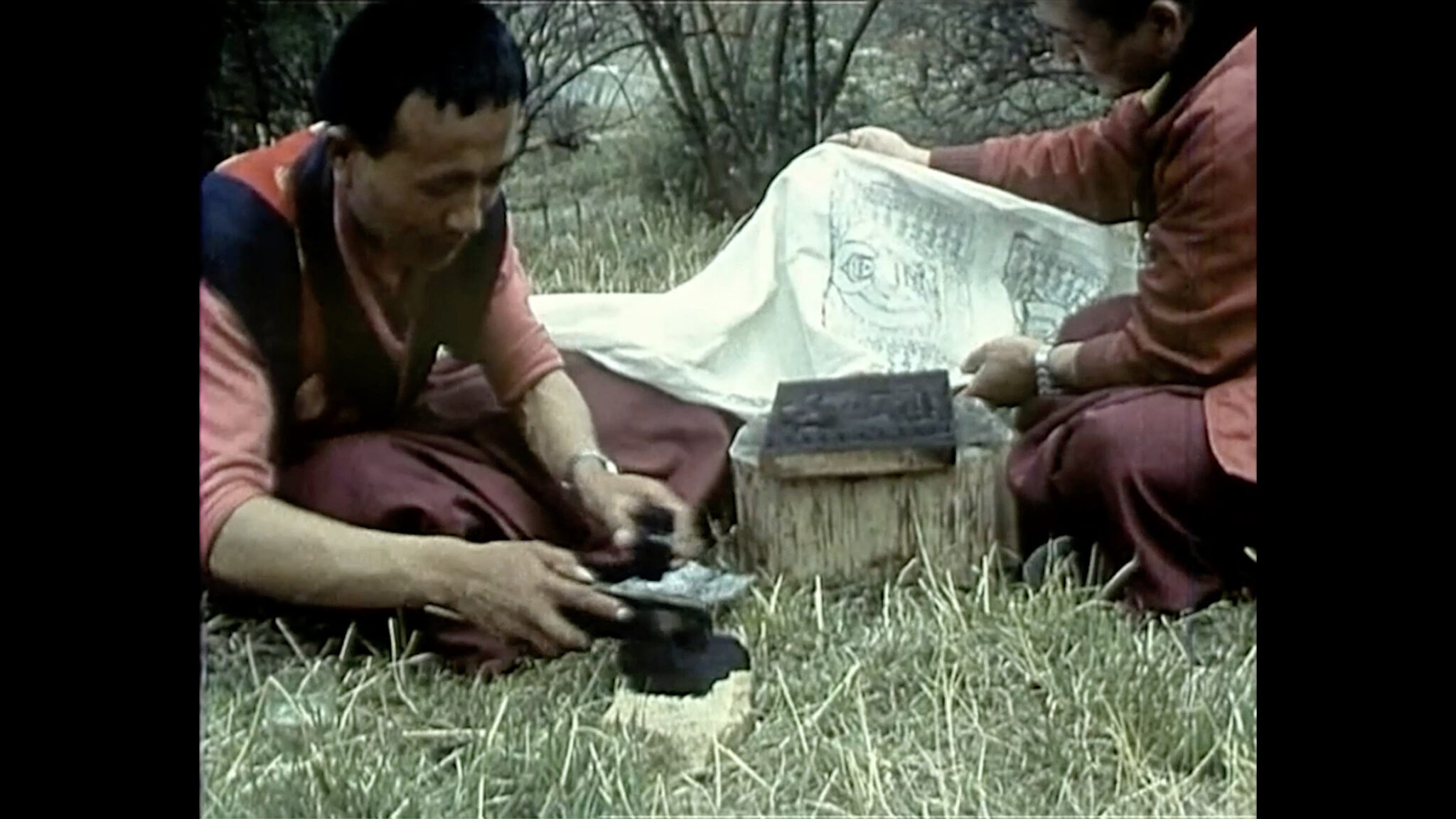

By the late twelfth century, printing became an important means of producing two-dimensional images printed in ink by using carved woodblocks on cloth or . Printing allowed for the mass-production of texts and images and the messages they carry. Later on, printing also led to the dissemination of visual compositions, such as narratives of the Buddha’s life or those that traced the previous lives of great religious masters, validating their authority.

First two folios from The Life of Milarepa; Ron Wosel Puk, Tibet; 1538; xylographic print on paper; each approx. 3-1/8 × 17¼ in. (8 × 44 cm); after A Brief Survey of the Evolution of Tibetan Printing Technology (Bod kyi shing spar lag rtsal gyi byung rim mdor bsdus), Bod ljongs bod yig dpe rnying dpe skrun khang, 2013

Leaves from a The Perfection of Wisdom (Prajnaparamita) Sutra manuscript; Nalanda Monastery, Bihar, India; 1073, 1151; ink and opaque watercolor on palm leaf; each approx. 2 7/8 × 22 3/8 in. (7.3 × 56.8 cm); Asia Society, New York; Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Acquisitions Fund; 1987.1; image courtesy Asia Society

Frontispiece from the Great Destroyer of the Thousand Foes (Mahasahasrapramardani) Sutra Manuscript; Tibet; ca. 13th–14th century; ink and pigments on paper; 7 1/4 × 27 in.; Rubin Museum of Art; C2004.33.1

The Rubin Museum of Art, "Carving Wood Blocks at the Degé Printing House," YouTube, January 19, 2023, 14:00, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_m45p8aSNF0.

The Rubin Museum of Art, "Making Paper at the Dége Printing House," YouTube, January 19, 2023, 16:41, https://youtu.be/watch?v=He62uO7qGl4.

A segment from Art religieux du Bhoutan (Religious Arts of Bhutan), the film by Marie-Noëlle Frei-Pont. Filmed on an 8mm film, 1974 to 1982. With kind permission of Marie-Noëlle Frei-Pont & Society Switzerland-Bhutan. The Rubin Museum of Art, "Art religieux du Bhoutan (Religious Arts of Bhutan) - Prayer Flag Printing," YouTube, July 6, 2023, 3:55, https://youtu.be/cP3YnnGERKg.

Textiles

Around the same time, textile made using , weaving, or embroidery were also known in Tibetan and Central Asian cultural spheres and became more prevalent as a luxury medium in later centuries. The additive process of appliqué by assembling shaped pieces of cloth allows for the creation of large-scale images several stories tall, which are displayed on the outer walls of monastery buildings or mountainsides during communal festivals. Production of such textile images required tremendous resources and large monasteries in Tibetan, Himalayan, and Mongolian regions with prominent patronage were famous for such religious thangkas. They were known as images that liberate through seeing.

Tibetan Buddhist images woven and embroidered in the costly medium of silk became characteristic of imperial courts in China, as statements of wealth and power, starting in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

TempleArtStudios, "Karmapa's Tsurphu Applique Project," YouTube, January 24, 2008, 6:22, https://youtube.com/watch?v=nfr7v-dRGrI

Achala; composition designed in Tangut Xixia, possibly produced/woven in Dingzhou (present-day Baoding, Hebei Province, China); early–mid-13th century; kesi silk tapestry with seed pearl; 35 3/8 × 22 in. (90 × 56 cm); Potala Palace Collection, Lhasa; image after Tibet Museum. 2001. Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House, 4

Vajrabhairava Mandala; probably Daidu (Beijing), China; Yuan dynasty; ca. 1329; silk and gold, tapestry with slits (kesi); 96 5/8 × 82 1/4 in. (245.5 × 209 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; 1992.54; CC0 – Creative Commons (CC0 1.0)

Jügdür (fl. late 19th–early 20th century); Begtse; Yekhe Khüriye, Mongolia; early 20th century; appliqué and embroidered thangka; 88⅛ × 69¾ in. (224 × 177 cm); Bogd Khan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar

Three-dimensional Images Permalink

Clay

Clay sculptures of varying sizes used to be the main form of three-dimensional image making in Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian regions. Unfired, molded and sculpted methods are used to create small and large statues.

Making of clay sculptures at a temple dedicated to Thangtong Gyalpo in Thimphu, Bhutan. A segment from Art religieux du Bhoutan (Religious Arts of Bhutan), the film by Marie-Noëlle Frei-Pont. Filmed on an 8mm film, 1974 to 1982. With kind permission of Marie-Noëlle Frei-Pont & Society Switzerland-Bhutan. The Rubin Museum, "Art religieux du Bhoutan (Religious Arts of Bhutan) - Clay Sculpture," YouTube, July 6, 2023, 16:31, https://youtu.be/o4BpAcTR_4c.

For smaller mass-produced devotional images, such as clay plaques known as , metal, fired clay, or wood molds are employed to stamp images in clay, sometimes mixed with medicinal substances or ashes of the deceased. Larger-scale clay are often constructed using the coiled strip method, with wooden armature to support the weight of the clay, and smaller details, like crowns or ornaments, made using molds. However, unfired clay is a less durable medium, and few older clay images survive and those at the center of ritual activity require frequent repair.

Content by Chandra Reedy, University of Delaware. Courtesy of the Bard Graduate Center, New York. Produced for the Agents of Faith: Votive Objects in Time and Place exhibition on view September 14, 2018 – January 6, 2019. Bard Graduate Center, "Tsa Tsa Making," YouTube, March 21, 2019, 5:49 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BX2DbFuqltc.

Metal

Metal became the prevalent medium for creating sculpture in the regions with the establishment of large-scale monastic institutions and the support of local rulers and emperors, especially from the thirteenth century onward. Nepalese artisans were particularly valued for their metal working skills and collaborated with Tibetan artists and patrons. Two primary techniques are metal casting using the lost-wax and both are still practiced in Nepalese, Bhutanese, Tibetan, and Mongolian regions. The process of , hammering sheets of thin metal, allows for the construction of large-scale , sometimes reaching over a story tall. The process of casting in Nepal is demonstrated and described in detail in the exhibition theme:lost-wax metal casting .

Queen as the Goddess Prajnaparamita; western Nepal/western Tibet; mid-14th century; gilt copper; height 8 in. (20. 5 cm); Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; F1986.23; image courtesy Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution

Vajrapani; Efi (efü?) khalkha süme, Shiliin Gol League (formerly in Chakhar), Inner Mongolia; mid-18th century; gilt-copper alloy with lacquer and pigments, inset with gems; height 73 in. (185.4 cm); Stockholm Ethnographical Museum (Folkens Museum Etnografiska); 1935.50.1714; photograph by John B. Taylor

Flying Naga; Nepal or Tibet; 14th century; Gilt copper alloy; repoussé; 13 1/4 × 15 3/4 × 2 1/8 in.; Rubin Museum of Art; C2005.16.18

The Stages of Nepalese Lost-Wax Metal Casting; Nepal; 2022; wax, clay, metal alloy; Rubin Museum of Art; SC2022.2.1–.6; Photograph by Sharif Hassan

The Rubin Museum of Art, "Lost-Wax Metal Casting," YouTube, June 26, 2023, 14:58, https://youtu.be/oKVUhV6Q3e8.

Stone

Stone is used less frequently than most materials and employed to create images in relief, sometimes carved into the on a large or small scale, or as standing plaques , as well as in the round and were often painted.

Wood

Wood is used depending on regional availability, and is often used for carving woodblocks for printing both texts and , covers for traditional , as well as architectural decoration.

Panjaranatha Mahakala; Tibet; 15th century; stone with pigments;10 1/8 × 7 1/8 × 4 1/8 in. (25.7 × 18.1 × 10.5 cm); Rubin Museum of Art; C2002.10.2 (HAR 65085)

Rock Carving of Four-Armed Bodhisattva Maitreya; Mulbekh, Ladakh, India; ca. 10th–11th century; stone, height approx. 25 ft. (7.62 m); photograph by R. Linrothe

Deshay Maru Jhya (Window without an Equal); Yetakha tol; Kathmandu, Nepal; ca. 18th century; wood; photograph by Sameer Tuladhar, 2021

Paper

Paper is sometimes employed in to make sculptures, and especially masks, due in part to its malleability and light weight.

Ngadak Puntsok Rigdzin (1592–1656); Lo Gekhar Monastery, Mustang, Nepal; mid-17th century; papier-mâché; height approx. 35½ in. (90 cm); photograph by C. Luczanits, 2014

Guru Padmasambha, the scholar manifestations of Padmasambhava; Lo Gekhar Monastery, Mustang, Nepal; mid-17th century; papier-mâché; 26¾ × 22-7/8 × 15¾ in. (68 × 58 × 40 cm); photograph by C. Luczanits, 2014

Ritual Dance Mask of Guru Dorje Drolo; Bhutan or southern Tibet; ca. 19th century; papier-mâché, polychrome, fabric; 14½ × 13½ × 10-1/8 in. (36.8 × 34.3 × 25.7 cm); Bruce Miller Collection; photograph by John Bigelow Taylor

Art making in Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian regions takes a wide range of forms, dependent in part on local resources and trade. Shared developments in technologies, such as printing, pigment production, metalworking, and weaving, informed artistic dialog across cultures. Finely crafted secular objects, such as robes, vessels, swords, saddles, and carpets, are also made, and often decorated with religious motifs as well.

Glossary Terms Permalink

iconometry

Iconometry means the measurement of icons or religious images. Especially in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, detailed manuals exist that use precise proportional measurements to standardize the iconography of major deities, and maintain their correct proportions, regardless of scale. These proportions are commonly expressed visually in artist manuals as iconometric grids.

A thangka is a Tibetan hanging scroll, usually painted on cotton, and then mounted in a silk brocade mount. Thangkas can also be textiles woven or assembled in the appliqué technique. Thangkas are often kept rolled up around a wooden dowel affixed to the bottom end of the silk mounting, which also helps keep the scroll flat when hung. Almost all thangkas show religious subjects. Similar paintings produced in Nepal are called “paubha.”

Religious painting, usually on cloth, in the form of a hanging scroll.

illumination

An illuminated manuscript is one that is adorned with images, designs, and decorative text. Unlike an “illustrated” text, the images in an illuminated text don’t necessarily show scenes from the story of the text.

appliqué

Appliqué is a technique of sewing patches of cloth, often silk or felt, onto a base to create a design or image. Used to make thangkas, carpets, and clothing, this technique allows for the creation of large-scale images, often hung from monastery walls or displayed on mountainsides as part of communal festivals and rituals. While the image may be designed by a Buddhist master, women are often involved in the creation of appliqués.

Kesi is a type of silk weaving known from China and eastern Central Asia, originally associated with the Sogdian and Uyghur peoples. Kesi uses raw silk for the warp and boiled silk of various colors for the weft, producing vivid blocks of color. As the finished surface has a carved-like effect, giving the textile a three-dimensional quality, the technique became known as kesi, which literally means “carved silk.” By the early thirteenth century, the Tanguts employed this luxury medium for the creation of Tibetan Buddhist icons, which would be emulated by other courts, such as the Mongols, Chinese, and Manchus.

lost-wax technique

The lost-wax technique is a metal casting method used in many Asian cultures. First, the sculptor shapes an image out of beeswax. Then layers of clay are applied to the wax model, from fine to coarse, creating a mold, usually in several parts. When the clay mold is heated, the clay hardens and the wax is drained out. The metalworker then pours molten metal into the empty space of the mold through the same channels the wax was poured out. When the metal has cooled and hardened, the clay mold is broken off, revealing the rough metal statue inside. This statue is often then polished, chiseled, combined with parts that were cast separately, gilded, inlaid with precious substances, and painted.

repoussé

Repoussé is a metal-working technique in which an artisan hammers the back side of a sheet of metal, indenting it outward to create an image in relief on the reverse face.

In Tibetan Buddhism, a tsatsa is a small sculpture created by pressing clay into a mold. Tsatsas can depict deities, stupas, auspicious signs, and more. Some tsatsas have medicinal plants, or the cremated ashes of loved ones mixed into the clay and taken to various sacred sites to generate merit for their better rebirth. In Newar context, a grain of rice is added. Tsatsas are created to generate religious merit and are often consecrated and then placed within stupas, or made by pilgrims and devotees and left at sacred sites. Tibetans have been creating tsatsas since around the eleventh century, and tsatsa making remains a common practice among lay devotees today.

engraving

Engraving is the process of incising lines, patterns, or writing into the surface of an object, such as a metal or wooden sculpture, or natural surface, such a stone.

papier-mâché

Papier-mâché is a sculpting technique that uses wet paper mixed with an adhesive. The paper can either be pulped and used to form a sculptable mass around a wire frame, or spread in strips over a pre-made backing. When the paper dries it forms a hard, light surface. Many Himalayan temple images and cham masks were made from papier-mâché, although due to the perishable nature of the material, fewer of these survive than sculptures in stone or metal.