Summary

In East Asia, Ushnishavijaya was the name of a powerful prayer, while in Tibetan Buddhism, this prayer was personified as a deity. Art historian Rob Linrothe examines the multicultural history of an Ushnishavijaya image carved into a cliff side on the east coast of China according to Tibetan and Nepalese iconography, and commissioned by a Tangut administrator working for the Mongol emperor Qubilai Khan. The image may have been created as part of long-life rituals for the emperor.

Key Terms

deity

Different Asian religious traditions posit different types of divine beings. Hindus generally believe in an all-encompassing God-like being, called Brahman. They also believe in a variety of other gods (deva), including Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. Early Buddhists denied the existence of a single, all-powerful creator god. Nevertheless, they always recognized a variety of powerful spirits, like gandharvas and nagas. Mahayana Buddhists came to see bodhisattvas as beings of enormous power, and buddhas themselves as cosmic beings with the ability to create entire universes. Buddhist and Bon traditions in Tibet worshiped a variety of other gods (Tib. lha), like the mountain gods, or gods of the land. According to Buddhist tradition, enlightened deities are seen as beyond the cycle of death and rebirth, whereas gods (including Hindu gods) are not.

In Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, a dharani is a short, Sanskrit language text or spell-like formulas thought to have protective power when written or recited out loud, often as part of a ritual. Often inscribed on objects or at sacred sites, their power through the written physical presence is associated with long life, purification, and protection. Dharanis are similar to mantras, but usually longer. One important dharani is the Ushnishavijaya Dharani. The Pancharaksha is another important text that contains five dharanis of protection.

donor

In Buddhist context, donor is a person who contributes to or commissions a religious work of art. This act is intended to increase merit on behalf of the benefactor and is dedicated to the benefit of all. It is also usually done for a specific purpose, such as longevity, prosperity, or well-being; to advance religious practice; or to ensure a good rebirth of a deceased relative, teacher, or friend. A similar practice is also known in Hinduism and Bon.

merit

In Buddhism, merit is accumulated positive karma, or positive actions, that lead to positive results, such as better rebirths. Buddhists gain merit by reciting mantras, donating to monasteries and those in need, performing pilgrimages, commissioning artworks, reproducing and reciting Buddhist texts, and other deeds with good intentions. It is believed that merit can also be transferred to others through rituals performed to gain merit for deceased family members help them achieve a better rebirth. Merit making is an important motivation for positive ritual action, and is a prerequisite for success of religious and even secular activity.

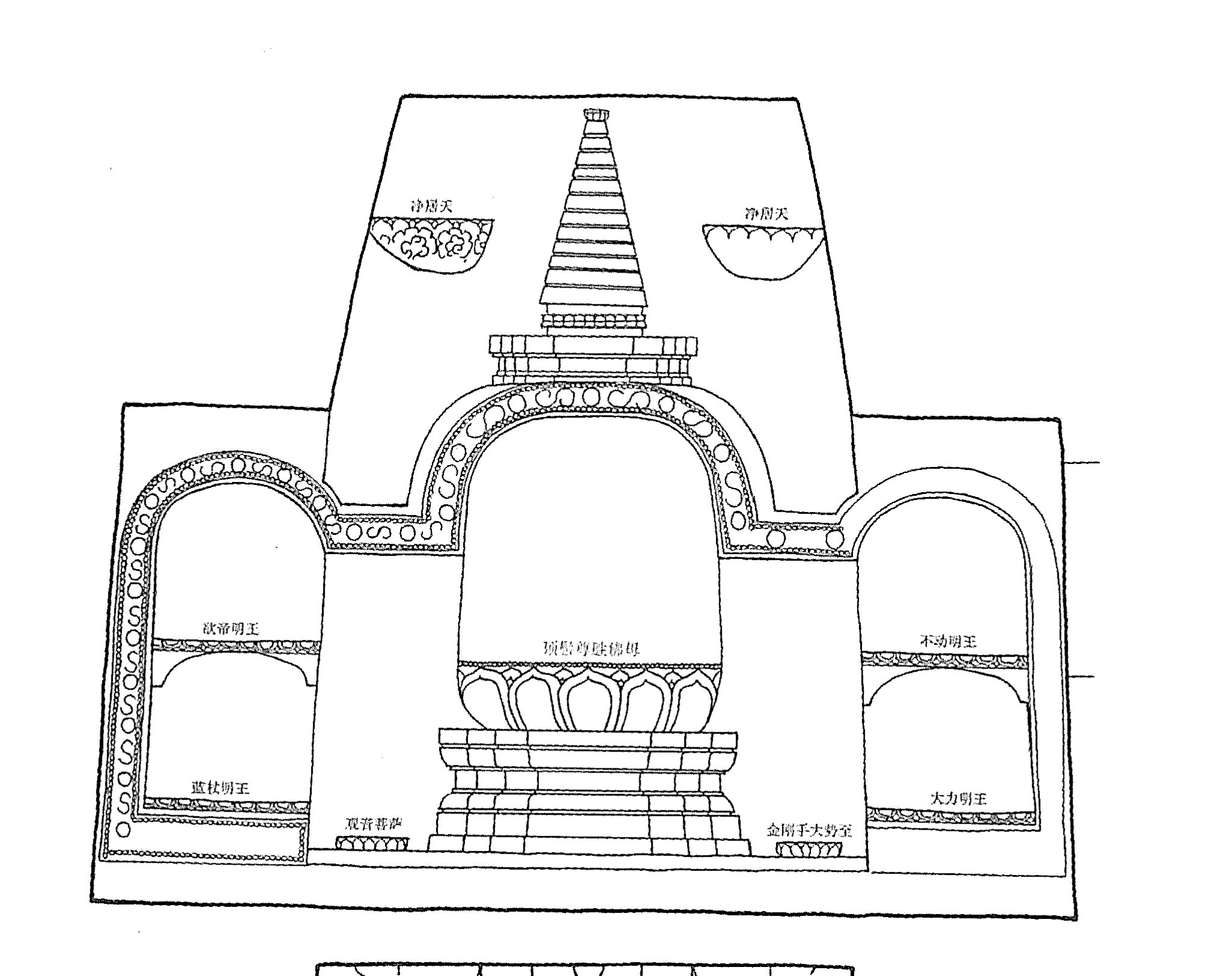

Stupas are monuments that initially contained cremated remains of Buddha Shakyamuni or important monks, his disciples, and subsequently other material and symbolic relics associated with the Buddha’s body, teaching, and enlightened mind. As representations of the Buddha’s presence in the world, stupas with their contents—texts, relics, tsatsas—continue to be important objects of Buddhist worship in their diverse forms of domed structures, multistoried pagodas, and portable sculptures. The original form of stupas was an earthen dome-shaped mound containing the remains in reliquary vessels or urns deposited within the innermost core. The dome would often be successively enlarged and surrounded by a path for a walk around in a clockwise direction and veneration (circumambulation)

The Tanguts were an ethnic group in medieval East-Central Asia, who called themselves Minyak and spoke a language distantly related to Tibetan. Between 1038 and 1227 CE the Tanguts ruled a state in what is now the Chinese provinces of Ningxia, Gansu, and Qinghai. This state took the Chinese dynastic name of Xia, also called Xixia “Western Xia.” The Tangut-Xixia emperors were major patrons of Buddhism, inviting both Chinese and Tibetan monks to teach in the capital, and instituting major Buddhist translation and printing projects in three languages. The Tangut state was destroyed by the armies of Chinggis Khan, leading to their absorption into the Mongol Empire, where many Tanguts served as officials.