Summary

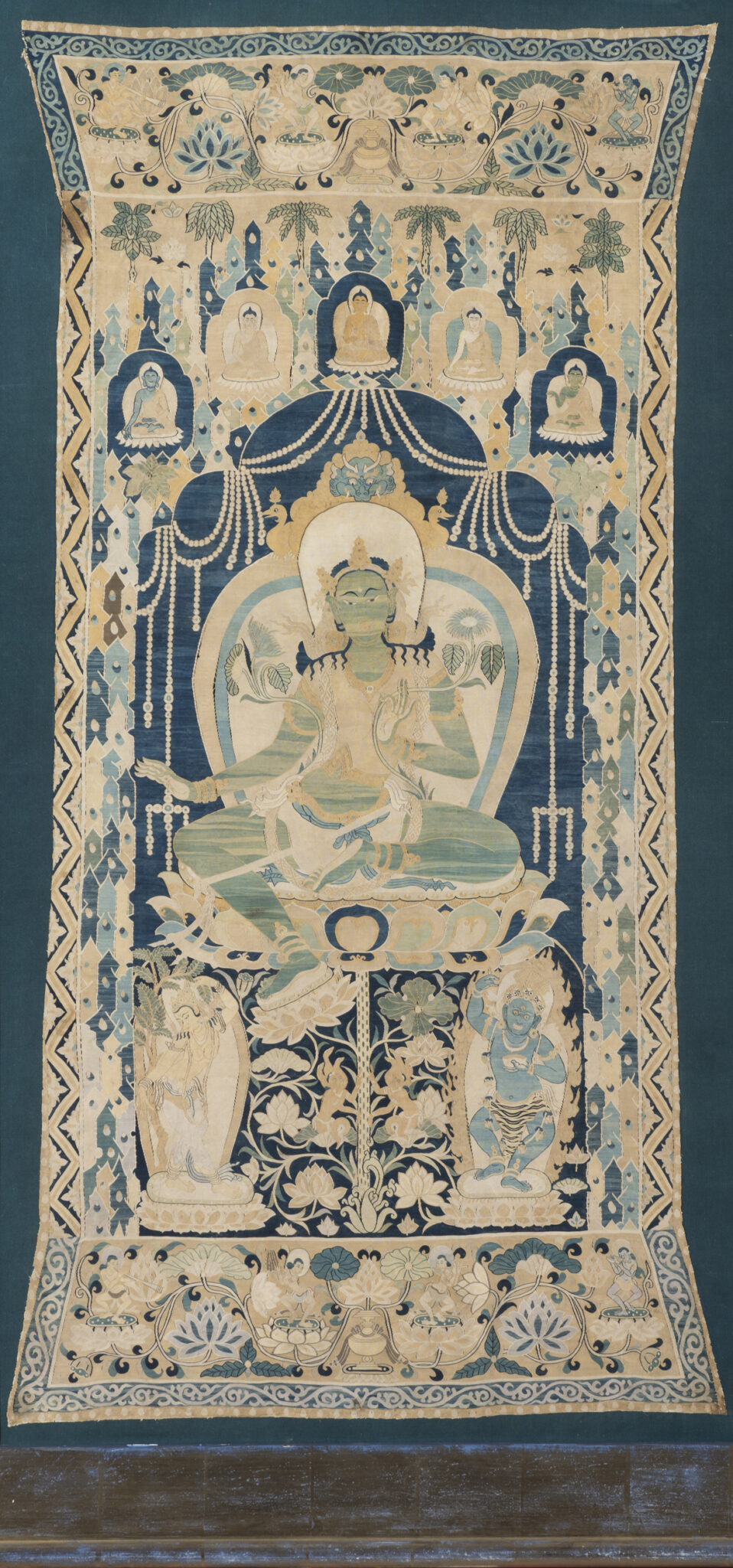

Art historian Yong Cho examines the origins of this silk tapestry of the tantric deity Vajrabhairava, commissioned by Mongol emperors and their wives according to the teachings of Tibetan masters. Mongolian court workshops adapted Central Asian weaving techniques to create these silk icons, which became a special focus of Mongolian court production. Such images may have hung in portrait halls within monasteries, referencing traditions of Buddhist kingship with the worship of Yuan dynasty imperial ancestors.

Key Terms

deity

Different Asian religious traditions posit different types of divine beings. Hindus generally believe in an all-encompassing God-like being, called Brahman. They also believe in a variety of other gods (deva), including Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. Early Buddhists denied the existence of a single, all-powerful creator god. Nevertheless, they always recognized a variety of powerful spirits, like gandharvas and nagas. Mahayana Buddhists came to see bodhisattvas as beings of enormous power, and buddhas themselves as cosmic beings with the ability to create entire universes. Buddhist and Bon traditions in Tibet worshiped a variety of other gods (Tib. lha), like the mountain gods, or gods of the land. According to Buddhist tradition, enlightened deities are seen as beyond the cycle of death and rebirth, whereas gods (including Hindu gods) are not.

donor

In Buddhist context, donor is a person who contributes to or commissions a religious work of art. This act is intended to increase merit on behalf of the benefactor and is dedicated to the benefit of all. It is also usually done for a specific purpose, such as longevity, prosperity, or well-being; to advance religious practice; or to ensure a good rebirth of a deceased relative, teacher, or friend. A similar practice is also known in Hinduism and Bon.

iconography

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

Kesi is a type of silk weaving known from China and eastern Central Asia, originally associated with the Sogdian and Uyghur peoples. Kesi uses raw silk for the warp and boiled silk of various colors for the weft, producing vivid blocks of color. As the finished surface has a carved-like effect, giving the textile a three-dimensional quality, the technique became known as kesi, which literally means “carved silk.” By the early thirteenth century, the Tanguts employed this luxury medium for the creation of Tibetan Buddhist icons, which would be emulated by other courts, such as the Mongols, Chinese, and Manchus.

wrathful

In Hinduism, Buddhism, and Bon, some gods and deities are shown with flaming hair, bulging eyes, mouths showing fangs, adorned with garlands of severed heads, and trampling enemies, real or metaphorical. In Tantric Buddhism, such deities are said to be wrathful manifestations of wisdom and method who assume fierce appearance to protect, remove or overcome mental afflictions blocking the path to enlightenment. Others are unenlightened, indigenous gods bound by oath to protect Buddhist traditions. Some female deities, or dakinis, like Vajrayogini, appear as semi-wrathful, in beatific form but bearing small fangs. In the Bon tradition, similarly to Tibetan Buddhism, wrathful deities can be emanations or represent local gods and sprits. In Hindu traditions, gods and goddesses can appear fierce, holding many weapons meant to overcome demons.

The Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) is the branch of the Mongol Empire in Asia. In 1260 when Qubilai Khan declared himself Great Khan, his realm included Mongolian, Chinese, Tangut, and Tibetan regions. In 1271 emperor Qubilai Khan proclaimed the Yuan dynasty on a Chinese model, employing Tibetan and Tangut monks. Tibetan Buddhism played an important role in the state, establishing a political model that would be emulated by later dynasties, including the Chinese Ming and Manchu Qing dynasties. The Mongols were major patrons of Tibetan institutions, and many Mongols converted to Tibetan Buddhism, though their interest declined with the fall of the empire.