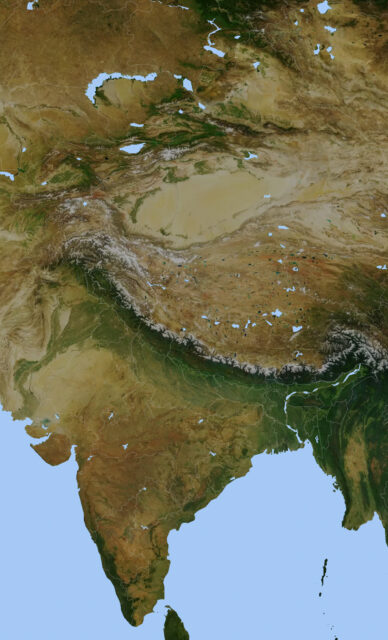

The Himalayan landscape is as varied as it is extraordinary—from jungle-choked river valleys to the world’s highest mountains, stretching north to the immense plateaus, deserts, and grasslands of Central Asia. The architectural traditions of the Himalayas are just as diverse and fascinating—India and Nepal are world famous for their intricately carved and many-tiered pagoda built from brick and wood. Tibet is known for its colossal fortresses and and stone and timber built to withstand ice storms, earthquakes, and enemy attacks. Further to the north, Mongolian nomads adorned their mobile tent-monasteries with woven or appliqué and carpets. Mongolia also partakes in the rich architectural heritage of China, famed for its delicate palaces and temples of timber and brick, built with sloping roofs and soaring eaves. Some architectural traditions are shared across the whole region, like Buddhist or , often elaborately painted and carved. Rich and poor houses alike keep shrine rooms or family altars where daily offerings are made to statues, paintings, and sacred relics.

Important types of sites that span all cultural zones of the Himalayas include:

- Palaces: opulent buildings where kings and powerful religious leaders live.

- : places where monks live, perform rituals, and meditate.

- : individual buildings which contain images of deities for worship.

- : domed tower-like structures specific to the Buddhist and Bon traditions, often containing relics and sacred objects.

- Caves and cliff : Caves are often carved into rock walls and filled with paintings. Some sites have monumental images cut into cliff .

- Household shrines: spaces reserved in family homes for daily devotion and ritual.

People across the Himalayan regions interacted with their surroundings driven by various motivations or purposes, developing diverse architectural styles. Numerous sites across the region reflect main themes of these intentional activities:

Marking the Natural World Permalink

The earliest known Himalayan art is carved into stones, marking the landscape with images of antelopes, yaks, tigers, and human hunters. Powerful local deities ruled the peril and fertility of the natural world—mountain peaks were the homes of warrior gods, while lakes and rivers were the domain of . With the rise of organized religions like Buddhism and Bon, old sites were inscribed with new meanings. Tibetan kings like Songtsen and tantric masters like built Buddhist temples to subdue spirits of the natural world. Old deities of place became protectors of the new faith. Visionary “treasure revealers” such as Dorje Lingpa wandered the Himalayan landscape, revealing hidden relics and sacred sites. Over time, Tibetan and Himalayan people developed elaborate systems of divination and geomancy to manage the forces of the land and the stars.

One of three striped carnivores carved on a boulder; Alchi, Ladakh, India; Iron Age (ca. 700–100 BCE); photograph by J. V. Bellezza

Mountain God Kula Khari; Tibet; 19th century; painted terracotta; 9-7/8 × 8¼ × 4-5/8 in. (25.1 × 21 × 11.7 cm); Rubin Museum of Art; C2002.7.3 (HAR 65079)

Spout of Golden Fountain of Bhaktapur Palace; Bhaktapur, Nepal; 1688; stone, repoussé metalwork; dimensions unknown; photograph by Christian Luczanits, 2010

Sites for the Nation Permalink

Himalayan religions were closely tied to powerful states. These kingdoms used art and architecture to mark the prestigious sites and outer territories of their rule. This could involve elaborate projects of patronage, like the royal monasteries built by the west-Tibetan king Yeshe or the early Ming emperors. This also produced new ways of connecting peoples and cultures across vast territories, like the elegantly functional Mongol Messenger’s Badge (Paiza or Gerege) in Pakpa Script that allowed officials of the Mongol Empire to requisition horses on postal roads from one end of Asia to the other. Sometimes the symbolic sites of historic empires inspired the development of national religious institutions. The Fifth Dalai Lama’s iconic Potala Palace in Lhasa was built on a mountain top said to have been home of the ancient Tibetan emperors, while Erdeni Juu monastery was founded amidst the ruined capital of the Mongol Khans.

Photograph by Prodhan (Sikkimese; dates unknown); The Potala Palace, Lhasa: The Seat of the Dalai Lamas; 1948; film negative; courtesy of Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente (Is.I.A.O.) in I.c.a. and Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale; Neg. dep. 7710/02 + 8037/05 © Museo delle Civiltà

Pilgrimage and Piety Permalink

Today we can view the world’s most sacred and far-flung places from our own homes with a tap of our fingers on a screen. A hundred years ago, people had to trek for years across the world’s highest mountains and harshest deserts for a single glimpse at some of these sites or objects. Many pilgrims hoped to reach the sacred city of Lhasa, seat of the Dalai Lamas and the famous Jowo Rinpoche. Other sites were famous for great yearly festivals, like the butter sculptures at Labrang monastery, or the procession of Bunga Dya through Patan city. Artistic industries served these communities, pilgrims, and institutional patrons. Multilingual maps were made to help travelers navigate Mount , the sacred realm of the bodhisattva Manjushri on earth. Scale models of the shrines like the Mahabodhi , or tracings of the footprints of the Buddha, allowed pilgrims to carry these sacred sites home with them when they returned.

Jowo Shakyamuni; northern India or Tibet; 500 BCE? or 11th century CE; about life-size; Rasa Trulnang Tsuklakhang (Jokhang Temple), Lhasa; photograph by Stefan Auth

Monk Lhundrub, engraver of Sanggai Aimag (Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia); Panoramic Map of Mount Wutai; Cifu Temple, Mount Wutai, China; 1846; woodblock print on linen, hand colored; 47 1/8 × 68 in. (119.7 × 172.7 cm); Rubin Museum of Art, Gift of Deborah Ashencaen; C2004.29.1 (HAR 65371)

Imagining the Universe Permalink

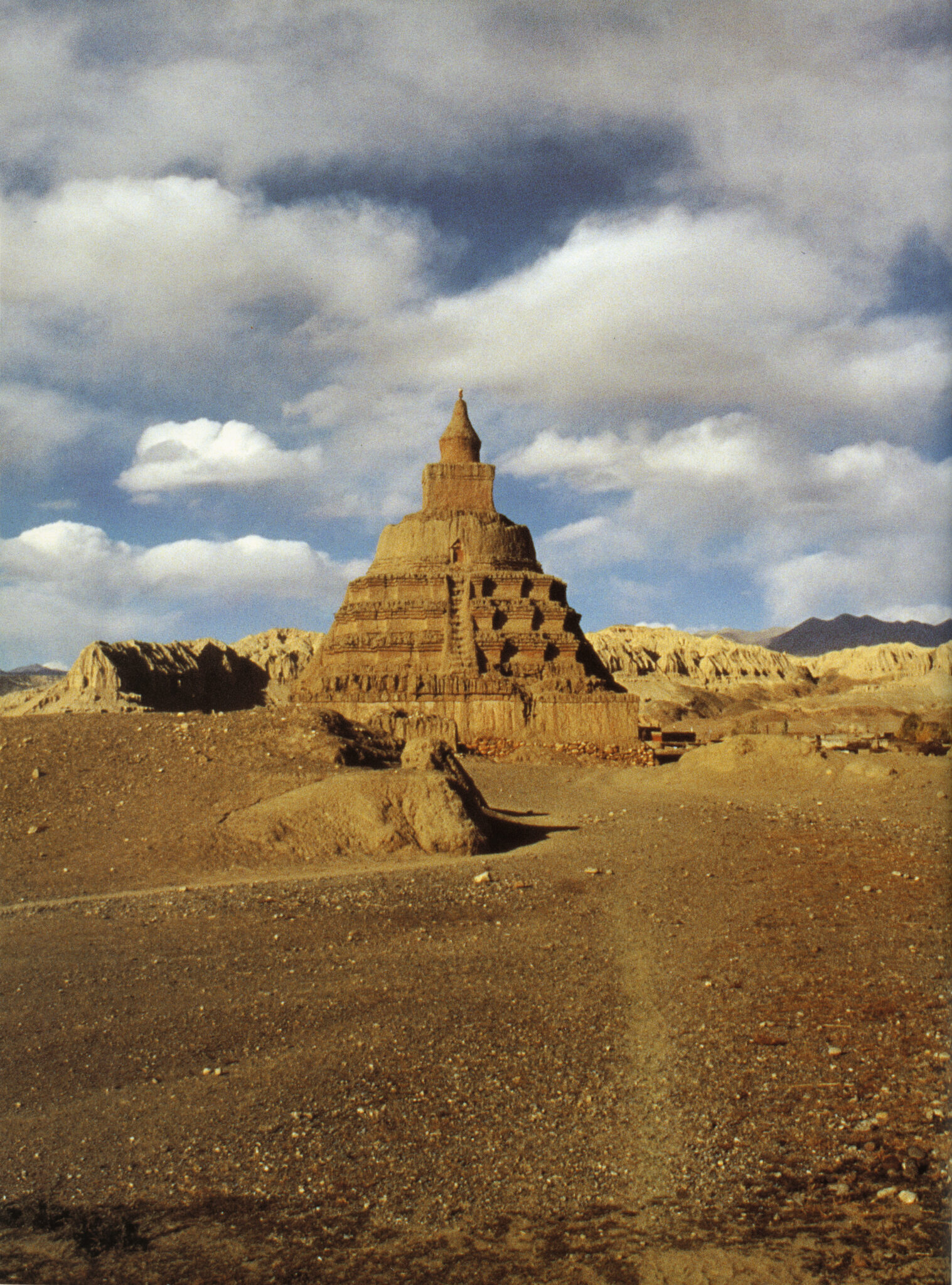

Sites and buildings helped people understand the world around them. Some sites were connected to mythic creation stories, like the Svayambhu Chaitya in Nepal, tied to legends about the creation of the Kathmandu valley itself. Other buildings modeled the universe. Elaborate stupas displayed vast pantheons of Buddhist . Temple halls with two- and three-dimensional mapped the realms of enlightenment. Laypeople learned about reincarnation in the Buddhist cosmos through “Wheel of Existence” images painted on the outer walls of monasteries.

Mahabodhi Temple at Bodhgaya, India; photograph by Christian Luczanits

Stupa at Toling Monastery; Ngari region, western Tibet (present-day TAR, China); 11th century; mud bricks and wood; photograph by Lionel Fournier

Kalachakra Palace Mandala; Potala Palace, Dukhor Lhakhang, Lhasa, Tibet; 1690s; gilt-brass repoussé, with cast figures, on wooden armature, with precious stone, crystal, and glass inlays; diam. 20 ft. 4 in. (6.2 m), height approx. 63 in. (1.6 m); photograph by Walter Gross, 1997

Wheel of Existence, detail showing image area; Tibet; early 20th century; pigments on cloth; image area 31-7/8 × 23-1/8 in. (81 × 58.7 cm), with brocade frame 65-5/8 × 40¾ × 1½ in. (166.7 × 103.5 × 3.8 cm); Rubin Museum of Art; C2004.21.1 (HAR65356)

These encounters with sites continue to change and develop in the modern era. In the twentieth century, the Tibetan thinker Gendun Chopel wrote about and painted depictions of his encounters on his journey through India, showing how modern geographical knowledge formed a new and powerful tool to understand the traditional sacred places of Buddhism. Today we explore the world in new ways, via “sites” such as museums, websites, and social media.

Glossary Terms Permalink

Bodhgaya is the site where the historical Buddha Shakyamuni is said to have attained enlightenment. Located in what is now the Indian state of Bihar, Bodhgaya is the site of the Bodhi Tree, the “diamond throne” (vajrasana), and the Mahabodhi Temple. Bodhgaya is arguably the most important pilgrimage site for Buddhists.

The Mahabodhi Temple is a temple at Bodhgaya, the site of the Buddha Shakyamuni’s awakening or enlightenment. The Mahabodhi temple is built near the Bodhi Tree under which Shakyamuni sat, marking that spot, known as the “diamond throne” (Skt. vajrasana) to commemorate his Awakening and its site. The peaked form of the temple dates from the Gupta period (fourth to sixth century CE), although the structure has been repaired and altered many times over the centuries. The Mahabodhi Temple is the most important Buddhist shrine and pilgrimage site. Large replicas, or representations of the Mahabodhi Temple have been built around the world and pilgrims took its small models to their home countries as souvenirs.

Beyul are concealed valleys said to be hidden throughout the Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau. “Treasure revealers,” or terton, are able to discover these realms, providing refuge for their followers in times of danger. Several regions of the Himalayas, including Sikkim, are said to have been populated by Tibetans as part of this process.

monastery

A monastery is a place where monks live, study, and perform ritual. It includes temples and other structures. Monasteries are central to Buddhism, and are also important in Bon, Hinduism, and Daoism. In Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian areas, some monasteries are enormous, wealthy, and powerful institutions, with branches of satellite monasteries forming networks across regions, often with thousands of monks, many decorated chapels, and huge holdings of land. Other monasteries, called hermitages, can be extremely simple, little more than a cave where hermits meditate. Generally, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery will have an assembly hall, several temples (Tib. lhakhang) for worship of specific deities, a protector chapel, as well as monks’ accommodations. A related institution in Newar Buddhism are the baha and bahi.

Baha and bahi are institutions in Newar Buddhism that have their origins in Indian Buddhist monasteries (Skt. vihara). By the twelfth-thirteenth century, celibate monasticism had gradually ceased to be practiced in Nepal. Descendants of monks known as Shakya, a name which references their kinship with Shakyamuni Buddha’s clan and monastic affiliation, retained control of the former monasteries (Newar “baha” and “bahi”) as family property passed down through paternal descent. Along with Vajracharya Buddhist priests, they comprise the Newar Buddhist sangha. The bahas and bahis remain the centers of Newar Buddhist life today, and usually consist of an open courtyard with a stupa at the center and a large temple building on the side opposite to the entrance.

Stupas are monuments that initially contained cremated remains of Buddha Shakyamuni or important monks, his disciples, and subsequently other material and symbolic relics associated with the Buddha’s body, teaching, and enlightened mind. As representations of the Buddha’s presence in the world, stupas with their contents—texts, relics, tsatsas—continue to be important objects of Buddhist worship in their diverse forms of domed structures, multistoried pagodas, and portable sculptures. The original form of stupas was an earthen dome-shaped mound containing the remains in reliquary vessels or urns deposited within the innermost core. The dome would often be successively enlarged and surrounded by a path for a walk around in a clockwise direction and veneration (circumambulation)

pagoda

Pagoda is an architectural form found all across South and East Asia. Pagodas are tall, tower-like structures with multiple tiers of sloping eaves, usually square or octagonal, and often get smaller with height. In Nepal and Tibet pagodas are usually used as temples. In China many pagodas functioned as stupas. Other pagodas are used as mosque minarets (towers used for the Islamic call to prayer).

Every monastery has a dukhang, or assembly hall, in which all the monks can gather for daily recitations of prayers and rituals. These are often grand pillared halls with walls covered in murals, with buddha-images and a throne for the abbot.

protector chapel

Most Tibetan monasteries will have a designated temple or chapel for the wrathful protector deities. Called “Gonkhang,” these chapels are often adorned with terrifying representations of ferocious spirits, flayed human bodies, and impure substances. These shrine spaces are used for rituals and offerings to protectors of the teachings and lineages, as well as local protectors who have been converted and bound by oath as protectors of Buddhism.

Torana is a Sanskrit word that usually refers to a gateway, but in Nepalese usage it is generally used for the decorative upper panel framing the top of a doorway (or other portal like a window), that embellish the entrances to shrines, temples, and Buddhist monasteries. Toranas in Nepal are typically adorned with mythological creatures, such as snake spirit (naga), water monster (makara), and the “sky face ” (kirtimukha). A set of six ornaments commonly found on Tibetan toranas are: a mythical bird (Garuda) at top, holding the tails of a pair of coiling snake spirits (naga), water monsters (makara), a pair of leogryphs, ridden by youths, supported by a pair elephants at the bottom.

circumambulation

Circumambulation means walking around something. Himalayan Buddhists often circumambulate as a form of veneration and generate/accrue merit by walking in a clockwise direction around stupas, monasteries, or sacred mountains. Bonpos do the same thing, except counter-clockwise.