Buddhist Sites & their Replicas

Gray Tuttle

Critical Questions Permalink

- Why were key Buddhist structures copied in each new cultural region into which the Buddhist teachings spread?

- How and why were some of these structures changed in the process of being replicated in their new settings?

- Are structures different from the images (of buddhas, bodhisattvas, etc.) that were replicated in new contexts as Buddhism was adopted in new cultures? If so, how?

Exhibition Permalink

Several objects in the exhibition lay the foundation for engaging with these questions before reading the essays in the Himalayan Art in 108 Objects publication.

Bodhisattvas

Avalokiteshvara

Tsongkapa

Stupa

Object Essays Permalink

Several essays in the publication give examples of structures that were copied.

Jokhang Temple, Lhasa

An example of Buddhist replication of the vihara of Nalanda India, which is copied in the layout of the Jokhang in Lhasa:

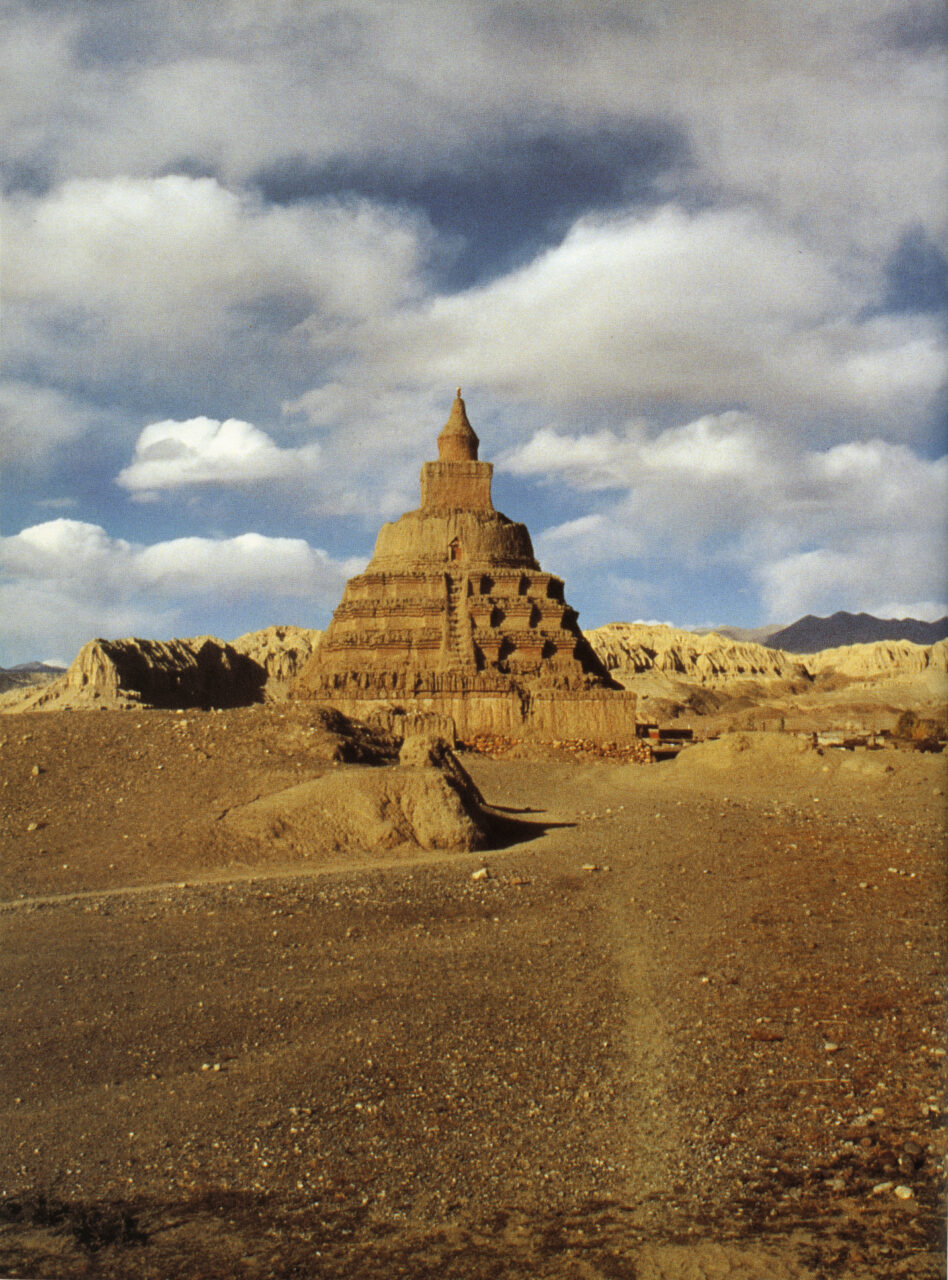

Stupa at Toling Monastery

Stupas took new forms (often several) in each new culture in which they were reproduced.

Mahabodhi Temple Model

Discussed below.

White Stupa, Attributed to Nepalese Artist Anige

This stupa was also copied later at Mount Wutai. See earlier exhibition on Wutaishan at the Rubin Museum of Art and 19th century Mongol map held by the Rubin, as described in: Wutai Mountain Pilgrimage Map.

Qutan Monastery (Drotsang Dorje Chang)

Rather than being a replication of a typical Buddhist structure, this site is marked by being a copy of a Chinese imperial style complex made to house Buddhist images. This trend of using Chinese architecture styles to house Buddhist images is repeated at Zhalu Monastery: Zhalu monastery mural [though maybe not discussed in the essay]), Dabaojigong Temple, Erdeni juu Monastery.

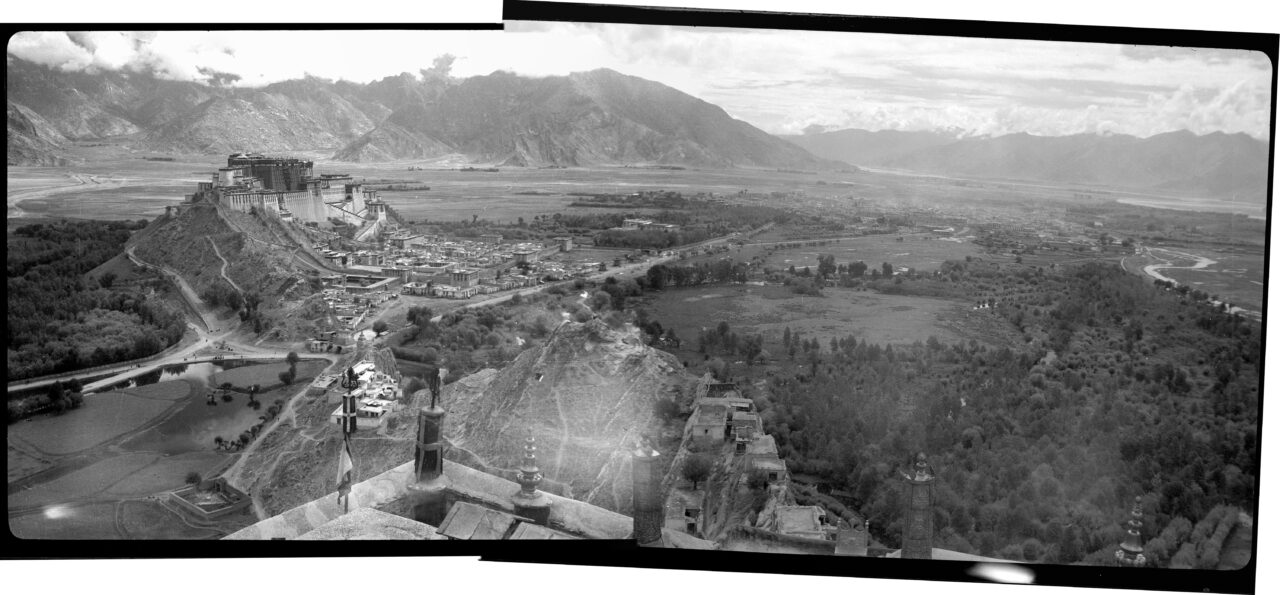

Potala Palace

The site of the Buddha’s Awakening, marked by the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya India is arguably the most important place in the history of Buddhism. So, it is no wonder that it is so often copied in forms both portable and monumental. As described by Elena Pakhoutova in Mahabodhi Temple Model, this pattern of replication has spread to Nepal, China, Mongolia, and Tibet.

To put the process of Buddhist replication/copying into perspective, the readings below are all about the Potala and all are oriented to the earthly home of a bodhisattva (an enlightened figure who chooses to stay on earth to help living beings). This bodhisattva is named Avalokiteshvara (or Chenrezik in Tibetan), and the original Potala is understood to be based on the island of Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean. This is the Potala that Longchenpa praises in his poem. Later, the Potala was “rebuilt” in Lhasa, as the great castle/temple of the Dalai Lamas (described in the Chayet and Bishop articles listed below). Finally, the Qing emperors built a third version of the Potala north of Beijing in a town called Chengde (the same site that is discussed in the Berger reading). Chengde also figures in the Zarrow reading about the Temple of the Happiness and Longevity of Mt. Sumeru (a reference both to Mt. Meru/Sumeru understood to be the center of the world and to the Tibetan monastery called Tashilhunpo, home to the other important Geluk lama, the Panchen Lama). There is another Potala “copy,” an island off the coast of China near Shanghai called Putuo shan. Finally, part of the Chinese copy of the Potala north of Beijing was copied yet again and sent the Chicago World Fair, as described below, in Ian MacCormack’s online post.

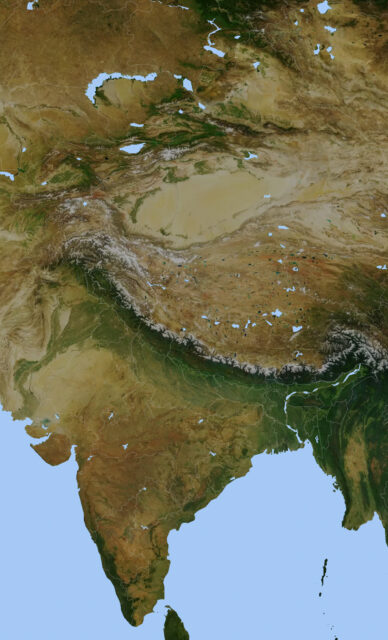

Locations of important sites mentioned above. Also visit the Interactive Map to see these essays placed in space.

Further Resources Permalink

Claire Sponsler, “In Transit: Theorizing Cultural Appropriation in Medieval Europe,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 32.1 (Winter 2002): 17–39

Anne Chayet, “The Potala, Symbol of the Power of the Dalai Lamas,” in Lhasa in the Seventeenth Century: The Capital of the Dalai Lamas, edited by Françoise Pommaret (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 3–-52.

Longchenpa and Herbert V. Guenther (trans). 1989. A Visionary Journey: The Story of the Wildwood Delights and the Story of the Mount Potala Delights. Boston: Shambhala. 17-25, 42-58.

Peter Zarrow (trans.), “Qianlong’s Inscription on the Founding of the Temple of the Happiness and Longevity of Mt. Sumeru (Xumifushou miao),” in Millward, James A., Ruth W. Dunnell, Mark C. Elliott, and Philippe Forêt. 2006. New Qing Imperial History the Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. London: Routledge Curzon. pp 185-188.

Ian MacCormack’s article on the reproduction of Potala Palaces, in Lhasa, Beijing and Chicago:

https://fairbank.fas.harvard.edu/research/blog/palaces-near-and-far-how-tibets-potala-palace-almost-came-to-harvard/ Links to an external site.

Patricia Berger, Empire of Emptiness: Buddhist Art and Political Authority in Qing China (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2003), 14–23, 177–82.

Peter Bishop, “Reading the Potala,” in Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places in Tibetan

Culture, ed. Toni Huber (Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1999), 367–85.

Glossary Terms Permalink

Avalokiteshvara, an embodiment of compassion, is a powerful bodhisattva, worshiped all across the Buddhist world. Avalokiteshvara is part of the very origin myth of the Tibetan people, and seen as the protector deity of Tibet. Many Tibetans believe that the emperor Songtsen Gampo, the Karmapas, and Dalai Lamas are all emanations of Avalokiteshvara. A special Avalokiteshvara image, the Pakpa Lokeshvara, is enshrined at the Potala Palace in Lhasa. In India and Tibet, Avalokiteshvara is understood as male, while in East Asian Buddhism, Avalokiteshvara is often thought of as female, and is known by the Chinese name Guanyin. Avalokiteshvara is recognizable in the Tibetan tradition by the lotus he holds, the image of Buddha Amitabha in his crown, and antelope skin over his shoulder.

In Buddhism and Bon, a buddha is understood as a being who practices good deeds for many lifetimes, and finally, through intense meditation, achieves nirvana, or ”awakening”—a state beyond suffering, free from the cycle of birth and death. “The Buddha” of our age is Shakyamuni, or Siddhartha Gautama. He is considered the founding teacher of the religion we call Buddhism. The buddha prior to Shakyamuni was called Dipamkara, and the next buddha will be Maitreya. These are known as Buddhas of the Three Times. Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhists believe that there are infinite buddhas in infinite universes, who have many bodies or emanations. Other important buddhas include Amitabha, Vairochana, Bhaishajyaguru, Maitreya, and many more.

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who has made a vow to become a buddha or awakened. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, many bodhisattvas are understood as deities with enormous powers who delay their final enlightenment, remaining in the phenomenal world to help suffering beings. Among such great bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya.

The Qing dynasty was a state that ruled in Eastern Asia from 1636 to 1912. Founded by the Manchus in 1644, the Qing armies crossed the Great Wall and began their conquest of the rest of the Chinese cultural region. By the 1750s the Qing empire had expanded to rule all of Mongolia, Tibet, and eastern Central Asia (including today’s Xinjiang), laying the groundwork for the modern state of China. The Qing governed Tibet and parts of Mongolia indirectly, in which the Manchu armies provided military support for local Buddhist governments like the Ganden Podrang. Tibetan and Mongol lamas were also extremely important in Qing court culture, and had close relationships with several Qing emperors.

Inner Asia

Inner Asia is a broad geographic term referring to diverse Mongolian regions including present-day Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, Buryatia, Tuva, and ancient territories traditionally occupied by Tangut and Manchu people, as well as areas of Western China. In some contexts Tibetan regions are also considered part of Inner Asia.

The Mahabodhi Temple is a temple at Bodhgaya, the site of the Buddha Shakyamuni’s awakening or enlightenment. The Mahabodhi temple is built near the Bodhi Tree under which Shakyamuni sat, marking that spot, known as the “diamond throne” (Skt. vajrasana) to commemorate his Awakening and its site. The peaked form of the temple dates from the Gupta period (fourth to sixth century CE), although the structure has been repaired and altered many times over the centuries. The Mahabodhi Temple is the most important Buddhist shrine and pilgrimage site. Large replicas, or representations of the Mahabodhi Temple have been built around the world and pilgrims took its small models to their home countries as souvenirs.

Manchus are an ethnic group originating in northeast Asia, roughly the area known as Manchuria. Historically known as Jurchens, in 1635 the ruler Hong Taiji (1592–1643) proclaimed the Qing Dynasty and officially changed the ethnic group’s name to “Manchu.” Qing emperors were said to be emanations of the bodhisattva Manjushri, and the name “Manchu” may relate to this. The Manchus formed the military aristocracy of this empire, which came to rule most of China, Mongolia, Tibet, and Eastern Central Asia until 1912. Many Manchus, including Qing emperors, had close political and spiritual relationships with Tibetan and Mongol lamas. Today the Manchus remain a major ethnic group within China, although very few people now speak the Manchu language.

merit

In Buddhism, merit is accumulated positive karma, or positive actions, that lead to positive results, such as better rebirths. Buddhists gain merit by reciting mantras, donating to monasteries and those in need, performing pilgrimages, commissioning artworks, reproducing and reciting Buddhist texts, and other deeds with good intentions. It is believed that merit can also be transferred to others through rituals performed to gain merit for deceased family members help them achieve a better rebirth. Merit making is an important motivation for positive ritual action, and is a prerequisite for success of religious and even secular activity.

Mount Potalaka is a semi-mythical mountain in southern India, said to be the abode of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara on earth. Many sacred sites have been named after this mountain, including the Potala Palace of the Dalai Lamas (said to be emanations of Avalokiteshvara).

The Panchen Lamas are an important tulku, or reincarnated lama lineage, in Tibet considered second in prestige within the Geluk tradition only to the Dalai Lamas. The Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682) declared that his tutor Lobzang Chokyi Gyeltsen (1570–1662) was the incarnation of Amitabha and granted him the title Panchen. Three “pre-incarnations” were identified, making Lobzang Chokyi Gyeltsen formally the fourth in the lineage. A special teacher-student relationship exists between the Dalai and Panchen lamas, when one passes away the other takes charge of identifying and educating the new incarnation. The traditional seat of the Panchen Lamas is Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse.

Stupas are monuments that initially contained cremated remains of Buddha Shakyamuni or important monks, his disciples, and subsequently other material and symbolic relics associated with the Buddha’s body, teaching, and enlightened mind. As representations of the Buddha’s presence in the world, stupas with their contents—texts, relics, tsatsas—continue to be important objects of Buddhist worship in their diverse forms of domed structures, multistoried pagodas, and portable sculptures. The original form of stupas was an earthen dome-shaped mound containing the remains in reliquary vessels or urns deposited within the innermost core. The dome would often be successively enlarged and surrounded by a path for a walk around in a clockwise direction and veneration (circumambulation)

Tibetan people

Tibetans are an ethnic group who live on the Tibetan plateau, as well as neighboring parts of northern India, Nepal, and around the world. Traditionally, Tibetans have combined agriculture in the river valleys with pastoral animal husbandry on high plateaus. Most Tibetans are Buddhists, but there are also followers of Bon, Islam, and other indigenous ritual traditions. Today, there are about seven million Tibetan people globally.

Tsenpo is a title, sometimes conventionally translated as “emperor,” used for the rulers of the Tibetan Empire. Songtsen Gampo (d. 649 CE) was the first tsenpo, who unified most of the Tibetan Plateau and founded the Buddhist Jokhang Temple in Lhasa. The last tsenpo of the Tibetan empire was Langdarma (d. 842), an anti-Buddhist king whose assassination by a Buddhist monk sparked civil war, and ultimately the collapse of the Tibetan empire. Later Tibetan rulers who tried to declare themselves inheritors of the Tibetan empire, such as the rulers of the kingdom of Tsongkha in eastern Tibet (eleventh century), also employed this title to strengthen their claims.

In Tibetan Buddhism, a tulku is a lineage of reincarnated lamas. Buddhists believe that sentient beings pass through infinite lives in samsara, reborn in new bodies after each death. Certain highly advanced practitioners are able to control this process, choosing their reincarnation. From the thirteenth century onward, this process became institutionalized in Tibet as a formal means of succession. When a tulku dies, a special team of monks and close disciples performs divinations and other tests to locate a child, who is then enthroned as the new incarnation of the lineage. Over the centuries, many of these lineages amassed immense estates (labrang), and became extremely powerful and prestigious within Tibetan and Mongol society. Important tulku lineages include the Karmapas, the Dalai Lamas, the Panchen Lamas, and the Jibzundambas.

Additional Keywords Permalink

- Jokhang

- Temple